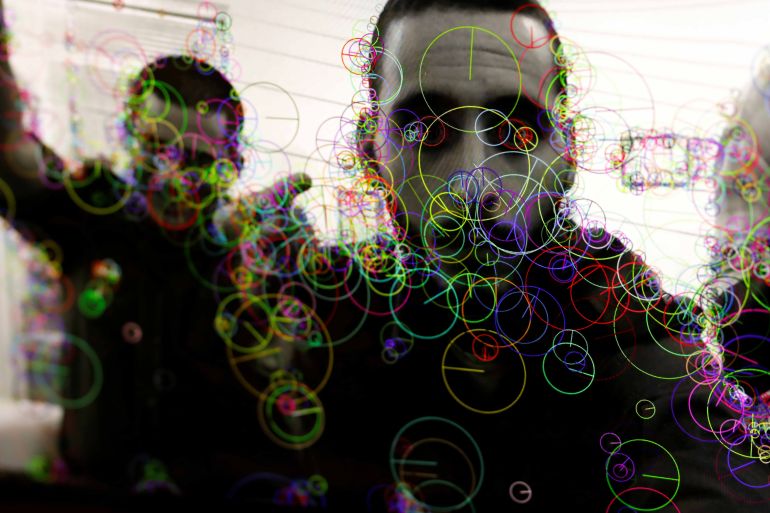

Biometric surveillance: Face-first plunge into dystopia

From the US to Israel, advances in biometric technology fortify systems of oppression.

Flying into Dallas Fort Worth International Airport from Mexico in December, I queued in the immigration line for US citizens and was taken aback when – rather than request my passport – the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agent simply instructed me to look at the camera and then pronounced my first name: “Maria?”

Feeling an abrupt violation of my entire bodily autonomy, I nodded – and reckoned that it was perhaps easy to lose track of the rapid dystopian devolution of the world when one had spent the past two years hanging out on a beach in Oaxaca.

A CBP poster promoting the transparent infringement on privacy was affixed to the airport wall, and featured a grey-haired man smiling suavely into the camera along with the text: “Our policies on privacy couldn’t be more transparent. Biometric Facial Comparison. Faster meets more secure.”

In my case, the process was not so fast, as I had to hand over my passport for physical scrutiny after I raised the agent’s suspicions by being unable to answer in any remotely coherent fashion the question of where I lived. My document was placed in a clunky plastic box, which I then had to cart over to a secondary inspection area for further interrogation. Channelling all of my energy into being as coherent and unsuspicious as possible, I was eventually sent on my way, the nation as secure as ever.

A special “Biometrics” section on the website of the CBP – a division of the US Department of Homeland Security – invites us to “Say hello to the new face of speed, security and safety”, and explains that “the use of Biometrics stems from the 9/11 Commission Report which instructed CBP to biometrically confirm visitors in and out of the U.S.”.

Biometric facial comparison technology is currently “deployed at 205 airports for air entry” and 32 for departure, as well as at 12 seaports and at “virtually all pedestrian and bus processing facilities” along the country’s northern and southern land frontiers. Between June 2017 and November 2021, more than 117 million people got to “say hello” to Big Brother at the US border.

As befitting any good business, CBP is concerned with customer satisfaction, and the website offers two samples of “What travellers say about CBP Biometrics”. The first is from an anonymous “airline traveller” who applauds this “fantastic invention” and contends that “the more the better”. The second is from a “cruise line traveller” who gushes: “We did this today, let me say it is awesome!! Through customs and outside in under one minute.”

But not everyone has such rave reviews of the biometric surveillance technology that is speedily conquering the planet with little oversight – and countless opportunities for the evisceration of civil liberties.

Consider, for example, a 2020 dispatch from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), titled: “Wrongfully Arrested Because Face Recognition Can’t Tell Black People Apart”. It tells the story of Robert Williams, a Black man locked up in Detroit due to an error in the face recognition software used by Michigan State Police. He was subsequently released, but the episode had lasting repercussions – including on his two small daughters, who, after witnessing the arrest, had “even taken to playing games involving arresting people, and … accused Robert of stealing things from them”.

As if Black people did not already have enough to deal with in a country that effectively criminalises Blackness – and where cops have proven themselves accordingly trigger-happy.

Indeed, while face surveillance technology has been exposed as wildly inaccurate, there is a much higher rate of misidentification of people of colour and women, which only stands to further exacerbate systemic inequality and discrimination. Immigrants, pro-justice activists, and other marginalised groups are also appealing targets for a profitable industry that is dangerously unregulated.

But as the ACLU observes, this technology “is dangerous when wrong, and it is dangerous when right”. In other words, eliminating technological inaccuracies will do nothing to ameliorate structural injustice, because “when you add a perfect technology to a broken and racist legal system, you only automate that system’s flaws and render it a more efficient tool of oppression”.

Speaking of efficiency of oppression, US partner in crime Israel continues to profit from its own racist system by globally marketing destructive technologies that have been battle-tested and perfected on the bodies of Palestinians – and biometric surveillance is no exception.

In 2019, NPR reported on the Israeli tech company AnyVision, the developer of both the facial recognition software utilised to identify Palestinians at Israeli military checkpoints in the West Bank as well as the technology deployed in a secret Israeli military surveillance project of West Bank Palestinians. According to NPR, AnyVision – which was at the time receiving funding from Microsoft – “wouldn’t identify its clients but said its technology is installed in hundreds of sites in over 40 countries”. Then-CEO Eylon Eshtein was quoted as follows: “I don’t operate in China. I also don’t sell in Africa or Russia. We only sell systems to democratic countries with proper governments.”

Given the Israeli army’s track record of, like, slaughtering 22 members of one Palestinian family in the Gaza Strip in one fell swoop, it seems democracy and propriety are perhaps overrated.

And the work goes on. As The Washington Post recently revealed, new developments in biometric surveillance are being put to the test in the West Bank, where Israel’s military has been “monitoring Palestinians by integrating facial recognition with a growing network of cameras and smartphones”. A smartphone technology dubbed Blue Wolf “captures photos of Palestinians’ faces and matches them to a database of images”, whereupon the app “flashes yellow, red or green to indicate whether the person should be detained, arrested immediately or allowed to pass”.

The extensive database was compiled via a competition by soldiers over who could photograph the most Palestinians, including children and the elderly, “with prizes for the most pictures collected by each unit”. Anyway, no one ever said mass surveillance was not great fun.

In the city of Hebron, meanwhile, a network of surveillance cameras monitors the population in real-time and can reportedly “sometimes see into private homes”. Yaser Abu Markhyah, a local resident, told the Post about an incident in which his daughter, aged six, “dropped a teaspoon from the family’s roof deck, and … soldiers came to his home soon after and said he was going to be cited for throwing stones”. How is that for accuracy?

From the US to Israel and beyond, the proliferation of invasive and abusive technologies is being swiftly normalised – literally in our faces – under the guise of security and efficiency. And as we plunge face-first into biometric dystopia, do not let anyone tell you it is “awesome”.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.