China can help end the war in Ukraine

But only if the US plays its cards right.

The ongoing war in Ukraine is the first global crisis where China, the great power, might serve as a mediator in the tripolar system.

Since the very beginning, Washington has not been treating China as an irrelevant party in this European crisis. Instead, it has been actively trying to divert Beijing from its chosen course of careful diplomacy.

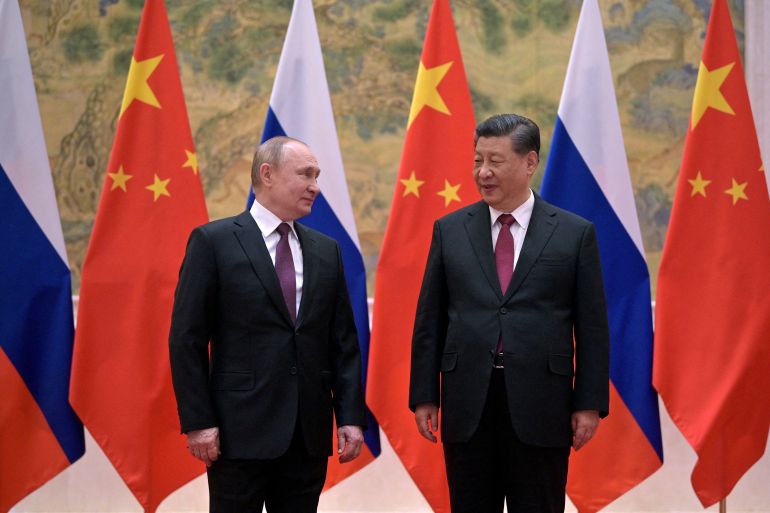

Indeed, a recent leak confirmed that US officials spent at least three months trying to persuade their Chinese counterparts to help them deter Russian President Vladimir Putin from invading Ukraine. And over a week into active conflict, the Americans are still eager to get the Chinese involved. After all, they know sanctions may not have sufficient impact on Russia without the support of the second-biggest economy in the world and that China’s Xi Jinping is perhaps the only person who can convince Putin to rethink his actions and alter his plans.

However, Washington is also aware of the fact that, when Russia and the US had a confrontation in the past, China has consistently chosen the path of careful diplomacy to protect its national interests. Nevertheless, today there appears to be a clear possibility to convince China to play an active role in the Ukraine crisis and help contain Moscow’s aggression.

Today, China supports the rules-based world order in which nation-state sovereignty is respected – it is not in favour of militarist revisionism or interventions. It also desires to maintain a stable relationship with the US, because the current political and economic status quo serves it well. China’s high-profile commemoration of the 50th anniversary of US President Nixon’s visit to Beijing last week was a display of such desire.

In this context, there is a reason for China to choose to be directly involved in the Ukraine crisis. And Beijing has already made some moves signalling this change in strategy. When the United Nations Security Council voted on a draft resolution on ending the Ukraine crisis, for example, China opted to abstain rather than vetoing it alongside Russia. The Western observes viewed this move as a success towards Russia’s international isolation. Furthermore, at least two of China’s largest state-owned banks (Bank of China and ICBC) announced their decision to restrict financing for purchases of Russian commodities on February 25.

On the same day, President Xi called Putin and encouraged him to negotiate with the Ukrainian government. This had an impact, and Moscow announced that it was ready for ceasefire negotiations. On February 28, when asked about Beijing’s stance on Ukraine, Wang Wenbin, the spokesman for the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said, “China and Russia are strategic partners, but not allies.” On March 3, China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank suspended and started reviewing all activities relating to Russia and Belarus.

So what are the missing pieces of the jigsaw to convince Beijing to use its influence over Moscow to mediate a ceasefire and eventually a peace agreement in Ukraine?

First of all, there is mistrust. Beijing does not believe it has much to gain from demonstrating strong support for Washington. Indeed, many Chinese analysts think the only “thank you” China will get for supporting the US in the Ukraine crisis would be increased Western support for Taiwan, a more aggressive NATO, and another round of anti-Chinese alliance building in its neighbourhood such as the AUKUS. It is an open secret that the priority of American diplomacy in Asia is building alliances against China. Beijing’s deep distrust of the US was perhaps the main reason why the Chinese officials initially dismissed the intel the Americans shared on Russia’s invasion plan as psychological warfare.

Another reason why Beijing is not yet fully convinced that it should involve itself in the Ukraine crisis alongside the West is that so far American strategists have only shown it sticks. The American administration and media have long been threatening to paint China with the same brush as the Russian aggressor if it does not agree to cooperate. Moreover, Washington has been pressuring India – a member of BRIC – to apply sanctions against Russia. If it succeeds, Beijing knows that it can much more easily present China to the global community as a force against peace.

To convince China to use its influence over Moscow to end this crisis, the US needs to start offering Beijing carrots. There is a need for a realist approach akin to the one successfully utilised by Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon half a century ago. To achieve peace, the tripolar system demands more prudence and less idealistic assumptions or messianism. Yet, after demonising China since Trump’s presidency, Washington might find it tricky to change public opinion right now.

In international relations, very often a stable balance of power is necessary for peace among conflicting powers. The West needs China to control a declining and revisionist Russia. And as it grows weaker, Russia will become more dependent on China’s economic support and security guarantees. As a result, China can easily guarantee the balance of power and be the mediator to end the current crisis. The world might only be missing a realist decision-maker like Kissinger or Nixon to help us cross the ideological trenches and build peace in Europe.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.