Kenya should have a serious discussion on marijuana legalisation

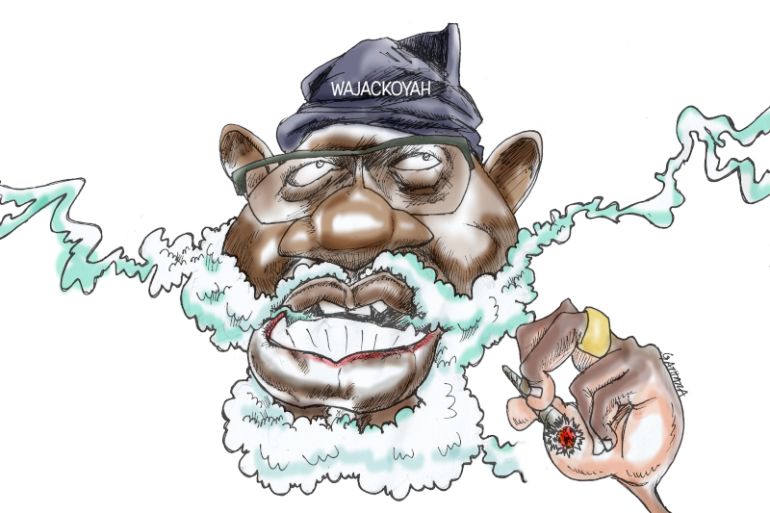

The likes of Professor George Wajackoyah should not be allowed to turn the legalisation debate into a political joke this election season.

Kenyan election campaigns have always thrown up their fair share of absurdities. The current one has been no different. In the course of it, we have learned that the electoral commission is bound to accept dubious documents from candidates for office because, the courts have ruled, it has no constitutional or legal mandate to verify their authenticity.

We have also learned how the incumbent president, Uhuru Kenyatta, was a tool for others’ ambition. We already knew that he nearly aborted his 2013 run due to what he claimed were “dark forces”. Four years later, we are now told, him nearly being slapped by his estranged deputy, William Ruto, was responsible for his staying on after the Supreme Court had annulled his re-election. In fact, the Ruto near-slap apparently also terrorised others in Kenyatta’s cabinet, with the defence cabinet secretary claiming he and his counterpart at the interior ministry had also had a close brush with it.

It is to be expected that once the elections are done and dusted, the outrageousness will die down somewhat and be forgotten. However, sometimes the craziness can open useful doors. Take the campaign of Professor George Wajackoyah for example. He has promised to make Kenya one of the richest countries in the world by exporting hyena testicles, snake venom and copious amounts of “ganja” (marijuana). The former policeman and intelligence agent under the brutal Moi dictatorship-turned academic has attracted 4 percent of would-be voters with promises to shorten the work week, suspend the constitution – arguing the United Kingdom is doing fine without one – appoint eight prime ministers, and carry out public hangings of the corrupt.

Many suspect him to be a state plant meant to draw votes away from Ruto and help out the campaign of Kenyatta’s former rival turned BFF, Raila Odinga, though the polls do not bear this out – he seems to be appealing mostly to the undecided. Whatever his intentions, Wajackoyah’s populist message regarding the legalisation of marijuana should be taken seriously as it opens the door to a more sensible public discussion of the country’s largely borrowed policy on drugs, which to date has been dominated by Bible-and-Quran-thumping religious types.

Previous efforts to have the discussion around marijuana legalisation have gotten little traction. And while the number of countries in the region that have legalised the growing and export of cannabis – estimated globally to be worth about $70bn by 2028 – has increased, only four on the entire continent have okayed it for local medical use, let alone recreational consumption. It is ironic that Africa seems content to export a product that relieves pain to the rest of the world while denying it to Africans on the basis of outdated puritanical tropes imported from those very countries.

It is worth remembering that the ban on marijuana and other psychotropic drugs did not originate on the continent. International drug control efforts can be traced back to the 1912 Hague Opium Convention that entered into force in 1919 and targeted opium, morphine, cocaine and heroin. Over the next half-century, a series of international agreements would expand the scope of the anti-drugs effort to include restrictions on cannabis (1925), synthetic narcotics (1948) and psychotropic substances (1971). Drug trafficking was made an international crime in 1936. Nearly no Africans took part in these decisions, as their countries existed as European colonial possessions at the time.

Nearly half were still under colonial rule in March 1961 when the US initiated the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, which sought to consolidate the various international agreements into one regime governing the global drugs trade, requiring controls over the cultivation of plants from which narcotics are derived, institutionalising prohibition and targets for abolishing traditional and quasi-medical uses of opium, coca and cannabis, and requiring countries to regulate not just production, manufacture and export, but also possession of drugs.

This is despite the fact that crops like marijuana had been widely farmed and smoked on the continent before the disaster of colonisation. Having grown up in a strict, US-driven prohibitionist regime, many African regimes, including Kenya’s, have little inkling of, and care even less about, their history or the interests and desires of their people, preferring to mouth the learned wisdom of US puritanism.

This is why Professor Wajackoyah, despite his antics and questionable motives, could be important. Already some in the political firmament are taking note of the support he is attracting and talking about decriminalising marijuana as a potent political issue. That suggests that, even after the election, there could be an opportunity to build on the momentum he has generated and to widen the conversation to cover all psychotropic drugs.

There is one danger though, and it is significant. If he were to go too far with his clowning, that could taint the entire argument for legalisation and turn it into something of a political joke. Rather than take that risk, it might be better for more sensible heads in media and policy circles not to wait till after the election but to start expanding the conversation now and grounding it on a more secure footing. That would ensure Kenyans continue discussing legalisation long after Wajackoyah has become a curious footnote in the history of the 2022 election.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.