BRICS expansion could be a bad idea. Here’s why

Taking in more members too quickly could leave BRICS incoherent, weakening rather than strengthening the bloc.

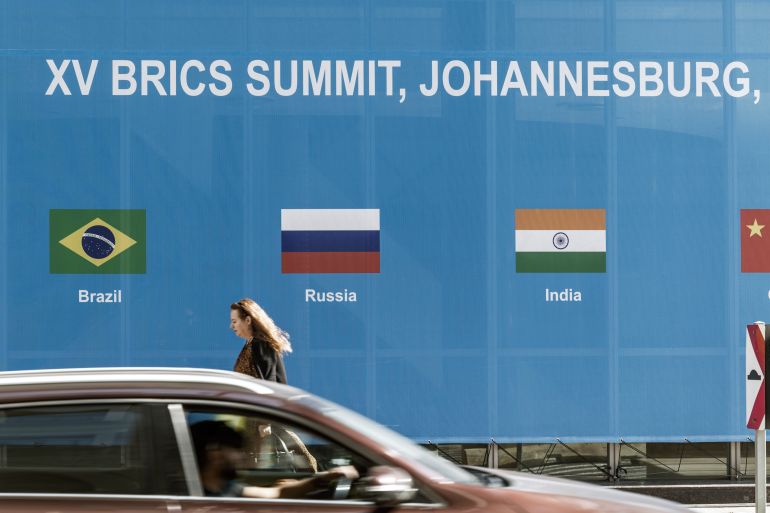

As leaders of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa meet for their annual BRICS summit starting on Tuesday, there is little doubt that the grouping has taken on new importance amid intensifying great power competition.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the West’s increasingly aggressive sanctions campaign against both Russia and China serve as the context in which the global diplomatic community will be watching the conclave in Johannesburg.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPhotos: Georgians ‘March for Europe’ in protest against controversial bill

Spain’s PM Pedro Sanchez to remain in office

US finds Putin probably did not order Navalny’s death in February: Report

Indeed, the war in Ukraine has already cast its shadow on the meeting. Russian President Vladimir Putin attending only virtually to avoid South Africa any embarrassment: The African nation is a member of the International Criminal Court, which has issued a warrant for Putin’s arrest on charges related to the conflict, and would legally be required to take the Russian leader into custody if he were to visit the country.

Yet with the possibility of any such drama now ruled out, two more substantive and interrelated developments will hold centre stage at the summit.

China and Russia have expressed interest in expanding the group in an effort to grant it greater weight in international affairs. Over 40 countries have expressed interest in joining the BRICS group with 22 formally requesting membership. These include Arab allies of the United States such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt, and rivals such as Iran. The list also includes countries from Africa, South America and Asia.

The second issue is de-dollarisation. China and Russia seem intent on using a larger BRICS forum as a focal point of their efforts to cut their dependence — and that of the global economy — on the US currency that has dominated cross-border invoicing and settlements since World War II. Beijing and Moscow are already conducting most of their trade in local currencies, especially the Chinese Yuan. Russia has pitched for a new BRICS currency, perhaps backed by gold, that would be used as an international medium of exchange between the members instead of the dollar.

For Russia and China, de-dollarisation has taken on fresh importance as they’ve increasingly come under sanctions from the West. Fear of how American and Western economic statecraft can damage their economies and limit their national security autonomy is a major issue of debate in both Moscow and Beijing.

But while South Africa, Brazil and India have better relations with the West, they too see lesser reliance on the dollar as being a positive for their economic growth and trade potential. Brazil’s President Luiz Inacio Lula de Silva recently stated that “[e]very night I ask myself why all countries have to base their trade on the dollar”.

To them, de-dollarisation is less about overthrowing King Dollar from atop the hierarchy of reserve currencies and more about carving out a separate method to transact between member states without the need for the dollar, the Western-based SWIFT messaging system and the services of New York banks. That being said, BRICS in its current form already represents 26 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) and 16 percent of global trade. So a successful effort in this regard is likely to have ripple effects.

But will this new currency gambit work?

There is too little known about the plan to reach definite conclusions. The BRICS track record on de-dollarisation has been mixed. China and Russia have successfully reduced their dependence on the dollar for cross-border trade. On the other hand, the New Development Bank, established by BRICS in large part to facilitate the de-dollarisation of state lending is largely dependent on the dollar and is now struggling to raise that currency due to having Russia as a founding member. Its chief financial officer recently acknowledged that “You cannot step outside of the dollar universe and operate in a parallel universe.”

The existing dollar hegemony is backed by an intensive network effect and a convenience factor. The stability of the dollar and deep dollar-denominated markets allow for predictability, ease of use and lower cross-border transactions. A new BRICS currency may address some of these challenges but certainly not all. There is also a significant imbalance in resolve regarding de-dollarisation within the grouping. Where sanctioned countries like Russia and China, as well as prospective members like Iran, are eager to disabuse the US of its ability to impose costly financial sanctions, others will be less inclined to bear the cost of such a transition.

Like the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation — which also includes China, Russia and India among its members — a key issue undermining the political impact of BRICS as a bloc is the complex nature of relations between its nations, and their differing approaches towards the West.

While they all dislike being called upon to abide by Western sanctions, many of them have strong relations with Western countries that they do not wish to hurt. India and China are strategic rivals that don’t see eye to eye on many issues. During last month’s SCO summit, India refused to sign on to a key economic document because it included Chinese diplomatic language like references to Beijing’s Global Development Initiative.

India has broadly aligned itself with Western interests against China. The availability of Western economic support and access to technology has increased significantly and West-India relations are experiencing a new era. This has significant economic benefits for India that make Modi very sensitive about being seen as empowering a counterbalance to the G7.

Brazil is being led by a left-wing president who is worried about alienating Washington as a business partner and is knowledgeable of how the US tends to take an aggressive posture against South American leaders who question its hegemony in the region.

South Africa is concerned that enhancing BRICS membership will further reduce its influence in the bloc. Officials in Pretoria are already concerned that other BRICS countries are far more influential in the group as its economic and social progress has stalled in recent years. South Africa is also very concerned about having to take sides in the emerging new Cold War between the US and China — though it is under a significant amount of pressure on South Africa to align itself with the West.

This is what has fuelled demands by India, Brazil and South Africa for stricter rules to determine whether an aspiring member should be allowed to join or even become an observer. India, in particular, has argued that democracies be the focus of membership considerations.

Such differences have undermined the work of other major global balancing organisations like the Organisation of the Islamic Cooperation, G77 and the Non-Aligned Movement, too.

The ascension of various other countries such as Argentina, Saudi Arabia and Nigeria, with their own complex foreign policy preferences, would not be seen favourably by Washington. But a rapidly expanded BRICS won’t necessarily be more powerful. Indeed, it could make the organisation more incoherent and unable to reach a clear consensus on anything of importance.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.