The judicial legacy of the Rwandan genocide: 30 years of double standards

The international community’s efforts to prosecute perpetrators of core crimes remain selective and politicised.

On the evening of April 6, 1994, the plane carrying Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana was shot down while approaching Kigali airport. Though Habyarimana’s assassins could not be identified, his death shattered the fragile peace between the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) defending the cause of the Tutsi and the country’s Hutu government.

During the 100 days that followed the attack, genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes were perpetrated on an unimaginable scale; nearly one million Tutsi civilians as well as moderate Hutus were slaughtered.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsEcuador sues Mexico at ICJ over granting asylum to former vice president

Germany launches trial of far-right coup plotters

The Abu Ghraib case is an important milestone for justice

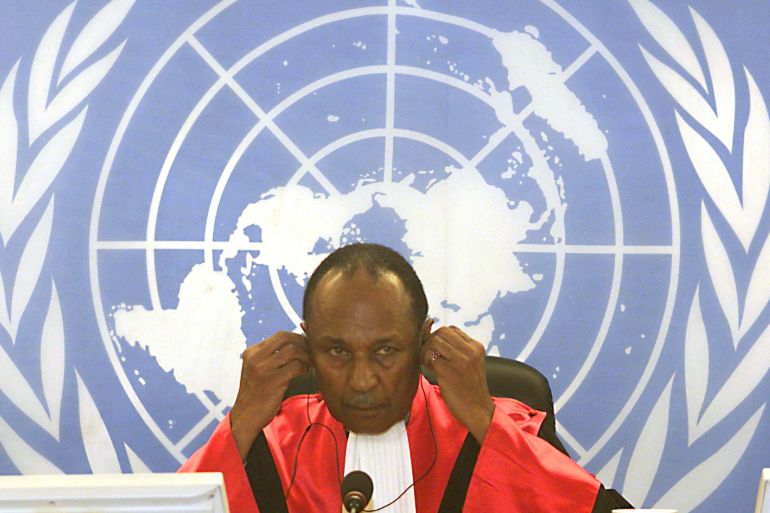

Following the indignation of the international community, the United Nations Security Council established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) to “prosecute persons responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law”. The ICTR indicted 93 individuals – three of whom remained at large – and delivered verdicts against perpetrators responsible for committing genocide. This was the first time in history, an international tribunal made such rulings.

As with its sister tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), ICTR’s emphasis on supranational jurisdiction aimed to contribute to a reconciliation process with the ultimate goal of helping Rwandans live side by side in peace again and deterring the perpetration of similar atrocities in the future.

Further international tribunals were established in other parts of the world after the genocide in Cambodia, the independence insurgency in Kosovo, the civil war in Sierra Leone and the murder of a former prime minister in Lebanon. These developments eventually led to the creation of the first permanent International Criminal Court (ICC) with a comprehensive mandate in terms of geography and time span.

What was considered a “cause of all humanity” for then United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan, must have seemed excessive to those countries who decided not to submit their territories to the ICC’s mandate – three of which (the United States, China and Russia) are the most prominent permanent members of the UN Security Council, the very entity that had initiated the movement towards international prosecution.

In the meantime, some European states had codified the principle of universal jurisdiction into domestic legislation, thus allowing their prosecutors to go after perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, even if such core crimes were committed abroad and even if offenders and victims were foreigners.

In 2001, for instance, Belgium inquired into core crimes committed in Guatemala and in Chad. These proceedings did not draw much political pushback from the international community as the events which had given reason to the Guatemalan investigations had taken place several decades before. As to the Chadian case, the accused former dictator Hissene Habre had been abandoned by his Western allies by then.

However, the situation altered dramatically when Belgian judicial authorities opened an investigation against Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon for massacres perpetrated during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. Two years later, a criminal complaint against US Commander Tommy Franks was filed for alleged war crimes committed in Iraq.

In June 2003, US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld threatened Belgium with losing its status as host to NATO’s headquarters if it did not rescind its legislation on universal jurisdiction. It did.

In 2013, a Spanish court ordered arrest warrants for former Chinese President Jiang Zemin, citing his responsibility for alleged human rights abuses in Tibet. China made it clear that there would be painful consequences on trade relations with Spain if the legislator in Madrid did not put an end to the avid use of universal jurisdiction. It did.

When in 2020 the ICC announced an investigation into potential war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during the Western invasion of Afghanistan in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, the US government went so far as to impose political and economic sanctions on ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda and her staff. Since then, and more than 20 years after the alleged crimes happened, the case is still stuck in the initial “investigation” phase.

The result of such manoeuvres is that, henceforth, a genocidaire does not qualify as a genocidaire through their acts but rather through the political interest of their prosecution among global powers.

Deterrence and the re-establishment of a peaceful order, the main goals of criminal proceedings, are being forfeited. The credibility of a fair and impartial international justice system is undermined.

Thirty years ago, the UN Security Council was determined to “take effective measures to bring to justice the persons who are responsible for [core crimes]”. The international community believed “that the establishment of an international tribunal for the prosecution of persons responsible for genocide […] will contribute to ensuring that such violations are halted and effectively redressed”.

Today, certain powers suggest the establishment of a special international tribunal with respect to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Others oppose this initiative and promote instead a multilateral investigation into Israel’s recent invasion of Gaza.

But unlike 30 years ago, it is not the victims’ interest that motivates either of the parties to put said criminals in the dock – it is only their own.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.