1971 India: ‘My heart tells me he is out there somewhere’

The story of the ace Indian Air Force pilot shot down over Pakistan during the 1971 war.

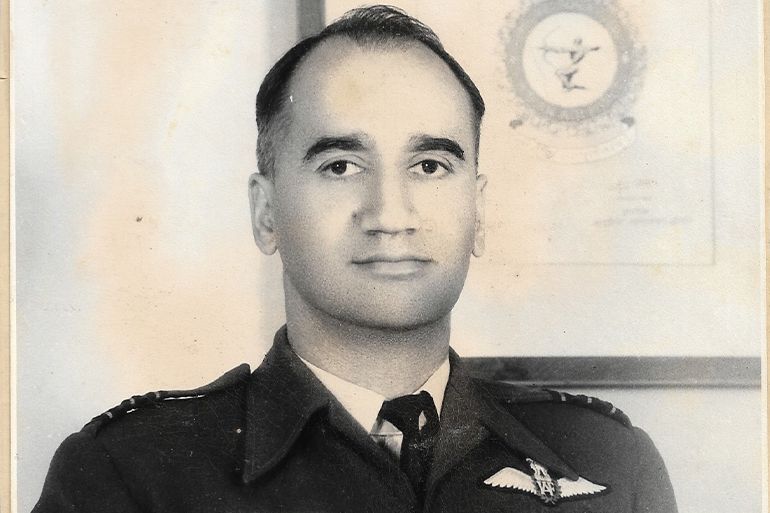

On December 13, 1971, Wing Commander Hersern Singh Gill, known as “High-Speed Gill” by his colleagues, had just returned from a strike mission on an underground Ops room and communication centre at Badin in Pakistan’s Sindh province.

He immediately went into a strategy meeting with the station commander of the Jamnagar air base, in India’s Gujarat state, from where his squadron of MiG fighters had been operating.

Keep reading

list of 4 items1971 Bangladesh: ‘None of them returned’

My father, a Pakistani prisoner of war in India

In Search of India’s Soul: From Mughals to Modi

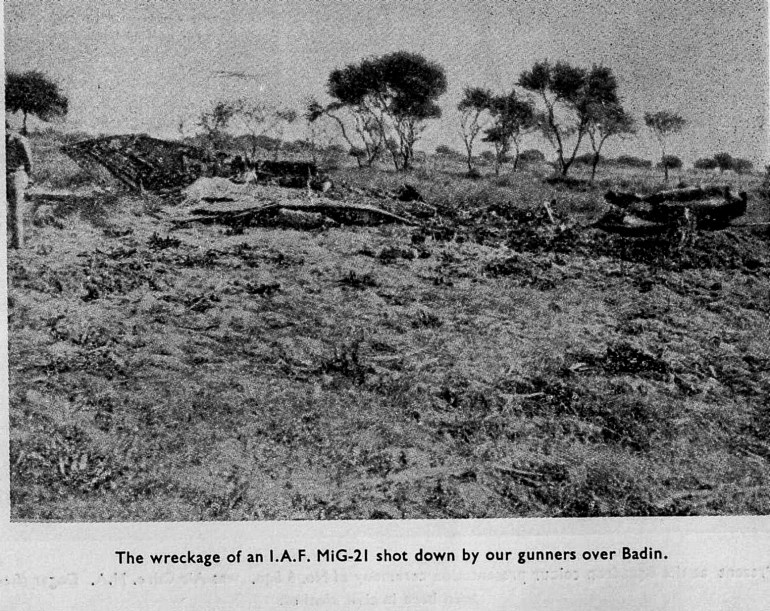

India and Pakistan had been at war with each other for 10 days – part of a conflict that would result in the independence of Bangladesh three days later, on December 16. Over the previous two days, Gill had conducted several air attacks on the heavily guarded Badin complex, but the Indian military’s 57mm rockets had been unable to penetrate its formidable concrete structure. At the meeting, it was decided to employ the more powerful S-24 rockets. But before the aircraft could be loaded with the new ammunition, the Western Air Command responsible for conducting air operations along the western front with Pakistan, ordered the squadron to carry out one more urgent strike.

Thirty-eight-year-old Gill, the commanding officer of No 47 Squadron (Black Archers), was angry and frustrated at the idea of going on another mission with the old ammunition. His wingman, Flight Lieutenant (later Air Commodore) IJS Boparai, recalled how he “was upset at not being given time to arm himself with the S-24 rockets because the bunkers at Badin were proving resistant as they were heavily protected with earthen embankments. A ring of 36 ack-ack guns also defended the signal complex.”

It would be a four-aircraft mission with two strike planes – one flown by Gill and the other by flight commander Squadron Leader Viney Kapila – and two escort planes, flown by Boparai and Flight Lieutenant BB Soni.

Kapila, who was organising the details of the flight, put his commanding officer Gill in the first strike aircraft and himself in the second. But Gill switched places with him. His flight mates were puzzled by his remark that: “The Black Archers must always come back with the leader.”

Some later suspected that Gill, who had already become somewhat of a legend in air force circles for his skill and the stunts he would perform, had had a premonition that he might not return.

Soon after the aircraft had released their bombs, Soni indicated that he was low on fuel, which was a signal for everyone to head back to base. But, as the others pulled away, Gill made one last, lone pass over the complex.

Realising that he could no longer see Gill’s aircraft, Boparai returned to the target area. On the ground below, he saw a dust trail, about one and a half kilometres long. Gill’s downed aircraft had scuffed along the ground before splitting into three parts – with the middle portion that had held the fuel tanks catching fire. Boparai saw no sign of a parachute but felt that Gill could have ejected from the plane.

That evening, a broadcast on Pakistan’s Hyderabad radio station announced that an ace Indian Air Force (IAF) pilot had been shot down over Badin and captured. It said the pilot was from the Hindon airbase (the peacetime location of Gill’s squadron).

An announcement later that day, however, said that Wing Commander Gill had died with the aircraft and could not be identified. A year later when Indian prisoners of war (POWs) captured on the western front were being repatriated, Indian authorities asked their Pakistani counterparts through the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which handled all communication regarding missing personnel, how they had known the pilot was Gill when his remains could not be identified. There was no answer and he is still listed as missing in action.

According to India’s official records, Pakistan took 616 POWs during the 14-day war, including 12 air force officers and eight civilians. India took 92,753 Pakistani POWs.

All POWs on both sides were finally repatriated after protracted negotiations stretching over three years. Once this had been completed, India began to compile a list of its soldiers who were still missing. It presented the first list to parliament in 1979. It contained 40 names, including that of Wing Commander Gill.

Pakistan has consistently denied that it holds any Indian POWs after the repatriations.

Remembering a man happiest in the sky

“Tall and wiry”, “a hard taskmaster” and “superbly fit” are how Gill’s former colleagues have described the passionate flyer who specialised in breathtaking aerobatics.

Gurbir Singh Gill, who has never stopped searching for his older brother, remembers him as being “happiest watching the sunrise from his perch up in the sky, in the cockpit of a MiG or a Hunter”.

Those who knew him well say that a pilot with such superb skills “who understood even the body language of the MiGs” could not have died unless there had been a direct hit to the cockpit.

Group Captain N Krishnamurthy, who is now retired, was an air traffic control officer who provided support to Gill several times and said in a tribute some years ago: “He evolved procedures – steeper approaches and higher speeds to get around the inherent limitations of the MiG.”

In 1972, Gill’s wife, Basanti, asked the Indian government to trace her missing husband. The IAF sent her the following information it had received from the ICRC, which was engaged in identifying, locating and helping to repatriate captured and displaced soldiers and civilians from all three warring countries – India, Pakistan and Bangladesh: “One MiG-21 aircraft was shot down near Badin on 13th December 1971. The pilot did not eject. The aircraft crashed and caught fire. The body or any other personal effects could not be recovered, therefore the identity of the pilot could only be established through Indian reports which declared him missing in that area. The radio report is incorrect.”

But the IAF was not convinced by this explanation and expressed its reservations to Basanti in a letter. It read: “If as the report states the identity of the pilot could only be established through Indian reports, then it would mean that his identity could only be established after 12th May 1972 when we first told the ICRC of the date/area in which your husband was missing. And yet, it was broadcast by Pakistani radio on 13th December 1971 that he has been captured. We have asked the Pakistan government to get further information to reconcile this discrepancy.”

Keeping hope alive

In the years that followed, Gill’s family never gave up hope that he might still be alive. Two accounts helped to fuel this hope.

Basanti’s sister was a flight attendant with the British Overseas Airways Corporation and in the late seventies, often flew from India to the United Kingdom via Pakistan. She struck up a friendship with a Pakistani flight attendant whose fiancé was from Badin. The colleague mentioned Gill’s case to his fiancé’s family and they told him a story about an Indian pilot who had ejected from his aircraft and landed near their home during the war. The Indian pilot had been captured. The family added an additional detail – that the captured pilot had been bald.

Basanti called Boparai, who relayed their conversation to this writer before Boparai died in 2019, to ask if it could have been Gill because, as far as she had been aware, her husband had not been bald. He told her that Gill had, indeed, shaved his head. “I confirmed to her that this was true and the realisation of what the news conveyed by the Pakistani flight attendant meant, shook us all,” he said.

Another account Boparai relayed was one he heard when working as an instructor in Baghdad from 1979 to 1981. It was a time when Iraq was rebuilding after the Baathist revolution and India had sent senior defence personnel to provide training at the country’s National Defence College. Boparai was among them. Some of the cadets he was teaching had returned from a training assignment in Italy, where soldiers from different countries were based as part of the United Nations. He said one of these cadets relayed a conversation he said he’d had with a US officer in Italy, in which the officer had mentioned an ace IAF pilot handed to the US after the 1971 war to help test MiG-21 aircraft.

It was a far-fetched story and one that could not be independently verified, but Boparai, who said Gill was the only ace MiG pilot who had been missing since the war, was not prepared to dismiss it completely.

If still alive, Gill would now be in his eighties. His wife and son died some years ago, but his 77-year-old brother Gurbir has not given up hope. Even now he rushes to verify any scrap of information he finds that could help him find out what happened to his brother.

“He is not just my elder brother, but my role model and best friend. He loved me dearly and despite the age gap, we shared a close bond,” he said. “So many years on, many people tell me that I should give up as he may not be alive any more. It may be a fruitless endeavour, but my heart tells me he is out there somewhere.”