1971 Pakistan: ‘I was born days after my dad died’

Fifty years on, a son remembers the father killed fighting in what was then East Pakistan, now Bangladesh.

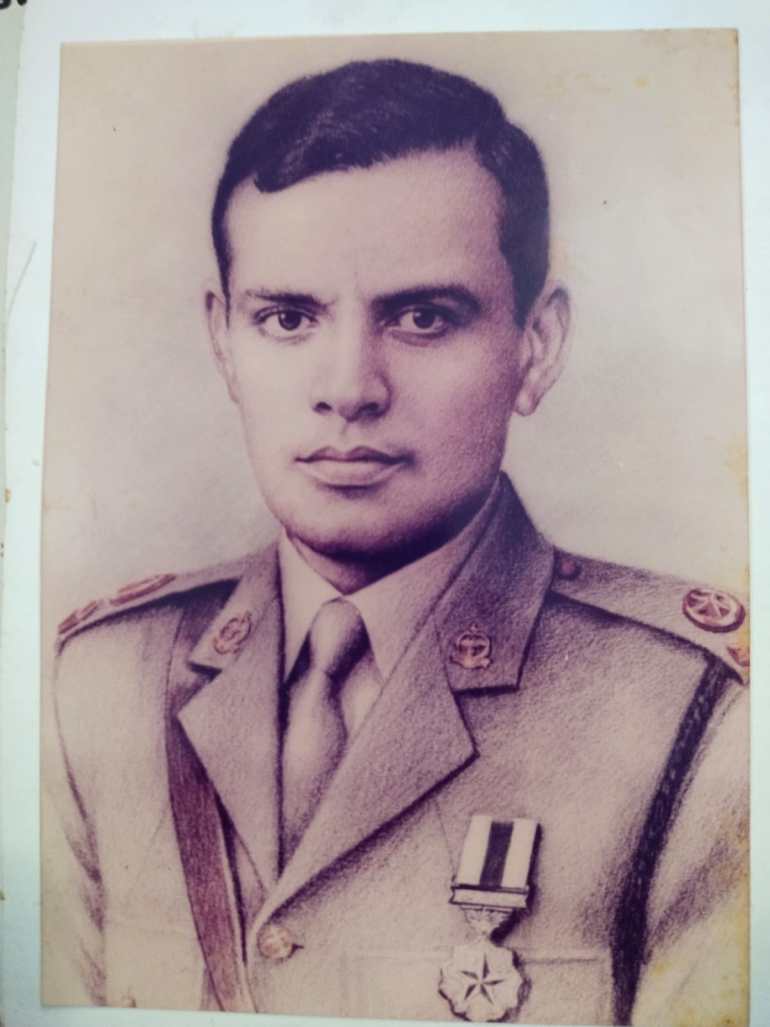

In the corner of Tariq Burney’s sun-lit drawing room, a black frame sits atop a glass cabinet. Inside it is a photograph of a sketch of a young man in military uniform — his face with its watchful gaze forever frozen in time.

The cabinet below displays a curious curation of family history: a black leather wallet, two watches and amber prayer beads, all carefully wrapped in cellophane bags.

Keep reading

list of 4 items1971 Bangladesh: ‘None of them returned’

My father, a Pakistani prisoner of war in India

What mental illness means to meThis article will be opened in a new browser window

The items once belonged to the man in the picture, Major Mumtaz Ali Burney.

“That’s my favourite photograph,” says Tariq, tenderly and with a sense of pride. “It gives me the feeling that he’s really seeing me.”

Tariq never met the man in the frame. “I was born 40 days after my father died,” he explains. But, he says, “he’s remained alive throughout my life, through the stories I’ve heard”.

Among those stories are accounts of how Mumtaz would defy social conventions to talk for hours on end to the doodhwala (milkman) and the barber (who would later grieve his death and keep his photo in his shop’s display for two decades).

“In those times class was an issue, and speaking to others from a different class was not the done thing – but he didn’t care,” Tariq explains, smiling proudly.

The conflict

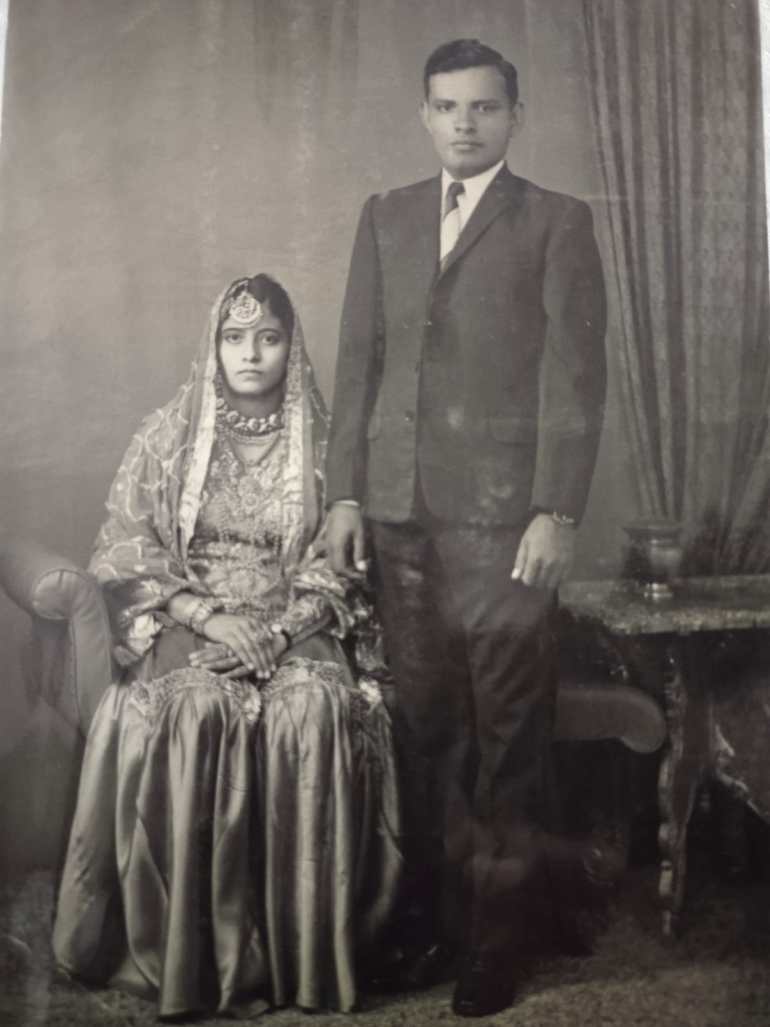

Major Mumtaz Ali Burney was 27 years old and recently married when he left Lahore in West Pakistan (now Pakistan) to fight in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

The two regions were once part of India under British colonial rule. But, in 1947, while the British were leaving, the Muslim minority in the Hindu majority country sought a homeland, dividing the territory into India and Pakistan – East and West. Up to two million people were killed in the violence and disruption that accompanied partition and many millions more were displaced.

Muslim-majority East Bengal became known as East Pakistan, and the western provinces bordering Iran and Afghanistan became West Pakistan.

But in the years after partition, there were riots and protests in East Pakistan over the central government being run from West Pakistan.

When East Pakistan’s Awami League won the 1970 general election under its leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, West Pakistan’s Peoples Party refused to recognise the result. Increasing violence between East Pakistan’s Bengali and Bihari (the Urdu-speaking community that had moved across from India during partition) communities accompanied the growing political tensions.

In March 1971, fighting between West and East Pakistan began as the latter pursued independence and the former held on.

Millions fled East Pakistan, crossing into neighbouring India.

The separatist movement in East Pakistan was supported by India, which officially entered the war on December 3, 1971.

Soon after, on December 16, the Pakistani army surrendered.

What became known as the Bangladesh Liberation War in that country was referred to as the Fall of Dhaka in Pakistan and largely ignored in the media and school history books.

“We don’t really mark December 16 as a nation, it was missing when we were growing up, skipped over in our education,” Tariq explains.

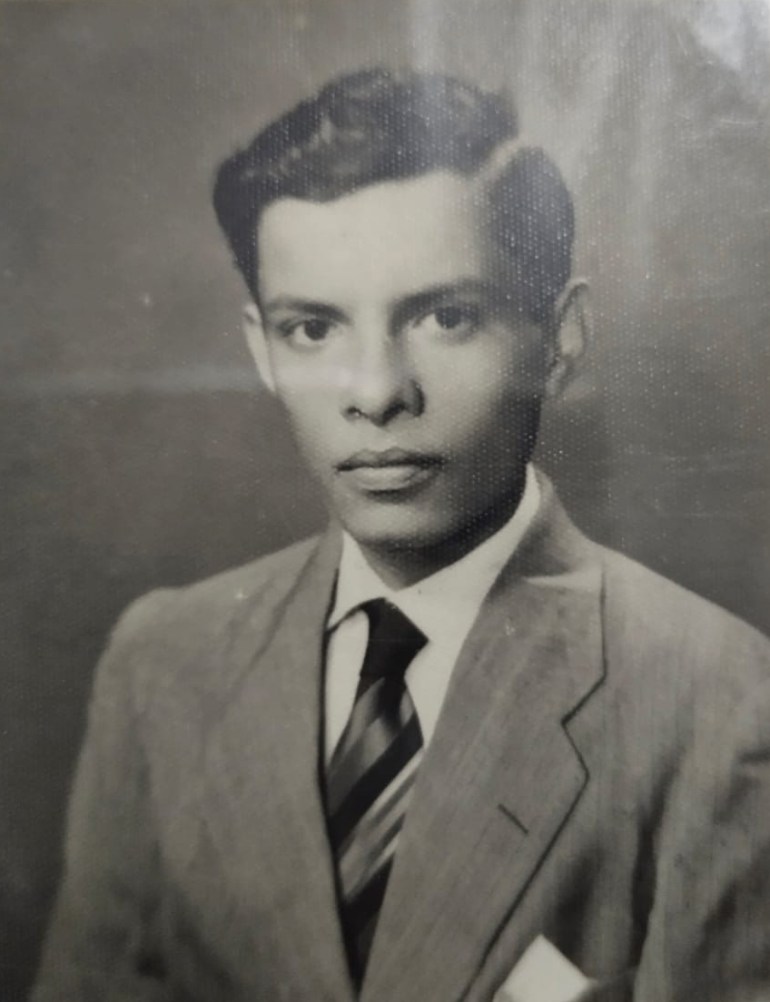

Inspired by the 1965 war between India and Pakistan, which both sides claimed to have won, Mumtaz had joined the Pakistani army in 1966. The business graduate who was always looking for a way to avoid studying too hard had told a cousin that he believed the army would offer him this, but that he had not realised how gruelling military life would be.

As the eldest of four brothers and a whole lot of cousins, the discipline of military service had offered Mumtaz, who had always been a father figure to the younger members of his family, an added sense of respect and responsibility.

A passionate soldier

Born in Amritsar in 1944, he had been a young child when his family had left India during partition, eventually settling 50km west in Lahore. “Those early years must have made an impression on a young mind who later wanted to serve his country the best he could,” Tariq reflects.

He was in the 16th Punjab Regiment but when he heard that the 30th Punjab Regiment was being deployed to Bangladesh, he asked to transfer to it.

The war had been raging for several months at this point and Mumtaz wanted to participate.

“When my grandfather Syed Isthiaq Ali Burney found out, he tried to convince my father to stay in West Pakistan, but noting his passion to serve the country he gave his blessing for him to go,” Tariq explains.

On September 8, 1971, Mumtaz took a train from Lahore to Karachi in the south of the country, and from there a military plane to Dhaka in East Pakistan with a battalion of around 800 men. Back in Lahore, his new wife, Shamim, prepared for the arrival of their first child.

“I like to think destiny took him there,” Tariq reflects.

Mumtaz wrote a letter to each family member, including his 21-year-old wife, from the front line.

She saved the letters, later laminating them and storing them safely away in a file, lovingly kept with his other belongings in the family drawing room.

“I know he was jubilant about my [imminent] arrival, and he mentioned it in a letter to Ami [mother], but I don’t pry or ask about this. There’s no need to make my mother relive that time. She’s 72 now, that time has gone,” he says pointedly.

‘All well’

On the afternoon of December 9, Tariq’s grandfather, who worked for the government’s textile inspection department, received a telegram. He had received two characteristically brief ones before, as it was the quickest way for soldiers to communicate during the war.

“All well, Mumtaz,” it read.

Those three words were the last they would hear from him.

Eleven days later, on December 20, another telegram arrived, this time from the Pakistani army stating that Major Mumtaz Burney had died in combat in the early hours of December 13, less than a week after his final message home.

According to the army’s account of his death, he had tried to protect his regiment from attack, using an anti-tank rifle on an advancing Indian tank setting it ablaze. But during the offensive, he was fatally hit in the liver by a tank shell.

He was taken to a field hospital for treatment, but died several hours later, becoming one of the thousands of soldiers who lost their lives during the war.

A day later, the Pakistan Armed Forces Eastern Command surrendered, and India took 93,000 Pakistani soldiers as prisoners of war.

Estimates of casualty figures in this conflict vary widely. Some state 26,000 soldiers from all sides lost their lives, while others put the military death toll at between 50,000 and 100,000. Anywhere between 300,000 and three million Bangladeshi civilians are thought to have been killed.

Tariq, which means morning star, was born soon after his father’s death in the same home his father had been raised in.

The large three-bedroomed apartment, shared by nine members of the family’s three generations, stood in Lahore’s Old City Anarkali neighbourhood, where historic Mughal-era buildings are nestled beside vibrant fabric shops and the sizzle of fresh samosas being fried in street eateries wafted through the air.

He fondly recalls his home as being one that was always filled with love, family, food and conversation.

His mother, a widow at just 21, had to fulfil the responsibilities of both parents. She was, he says, “everything”. She never remarried.

“Ami-ji sacrificed her life for me, she made sure I studied, always encouraging me to be more, to do better,” he says, in a voice filled with gratitude.

Tariq also credits his Dada (paternal grandfather), for shaping him as a person.

“He took me by the finger and guided me, taught me the way I have to move through society. My punctuality, my time-keeping skills, I learnt from him,” he says, closing his eyes as he remembers his late grandfather.

‘I feel his presence’

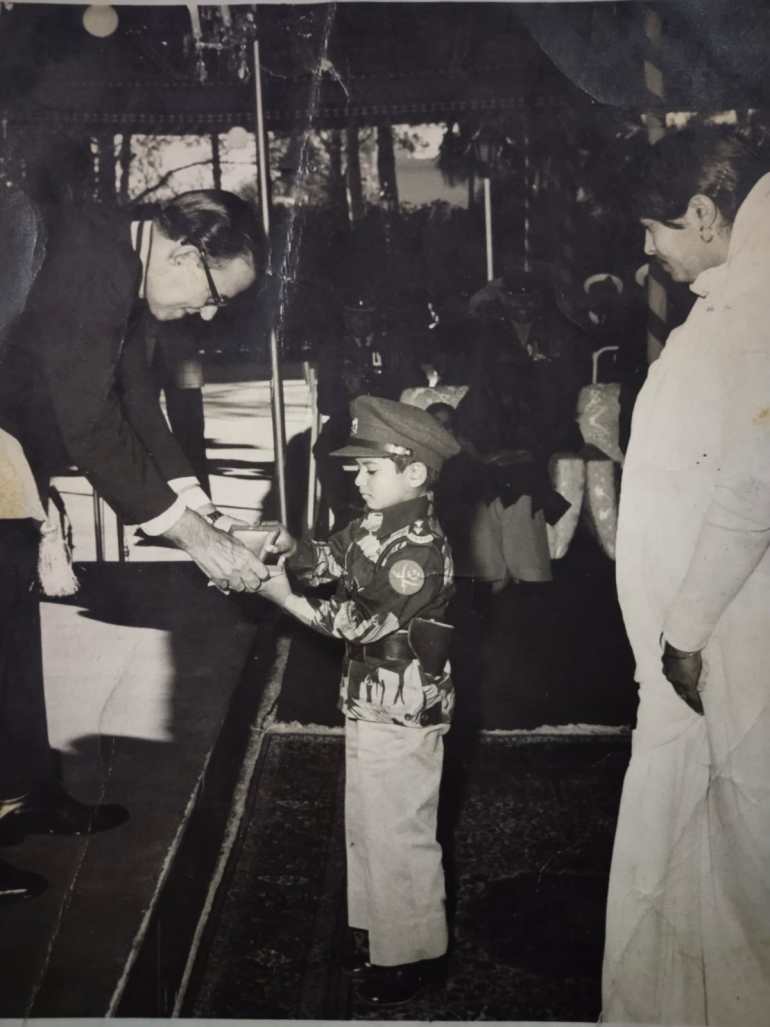

Tariq says he first understood that he did not have a father when he was five years old. He had been invited to receive the Sitara-e-Jurat, Pakistan’s third-highest military award, on behalf of his father for his leadership and bravery in combat in East Pakistan. The award, which translates to Star of Courage, was presented to a young Tariq by then-President Fazal Elahi at a military ceremony in 1976.

As he looked around and saw the “grown-up military men” in attendance, he realised that he was “the only child receiving an award for a father who wasn’t there”.

But it was his family’s conversations that would allow him his first glimpse into the man he had never met. “They’d speak amongst themselves and I’d absorb who he was through the stories – if I had a particular question it would be answered, but otherwise he wasn’t always spoken about.”

The family he did have filled any void that may have been left, he says, describing his childhood as full and happy.

“Playgrounds surrounded the flat and we had a good community around us – we’d sleep in the courtyard outside with a fan to escape the summer heat – I’ve got great memories of my childhood – it was full. I often still dream about that home.

“I don’t dream of my father, although I do feel his presence – on many, many, occasions. When faced with difficult moments in life, somehow, from somewhere things get done. That’s when I feel him, I know he’s around.”

What he doesn’t know is where his father is buried.

“All we know is that he had a proper burial … at the time of the war every soldier who died in combat was buried in a grave, all burials were marked as unknown soldiers,” says Tariq.

“Back then there was no concept of bringing anyone home, and the political situation wasn’t conducive to even make such a request.”

Soldiers buried each other.

There are no public records documenting how many soldiers were buried in unmarked graves. At the time, Pakistan wanted to move on from the defeat, which it found humiliating and diplomatic relations with its newly independent neighbour were tense.

This year, however, Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan and Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina congratulated each other on their respective countries’ Independence days.

“It’s not that we’re looking for the body, it’s been 50 years now, but it’s about having a form of physical connection to the grave, to know what it looks like rather than just imagine it, to pay respects to my father’s final resting place,” Tariq says.