On the front lines of the Myanmar military’s crackdown

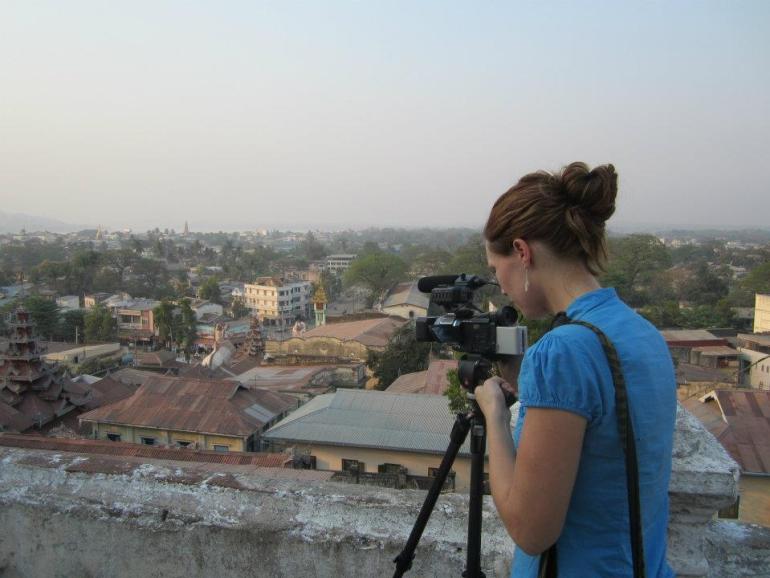

Reporter Ali Fowle reveals what it is like on the ground when protesters are being shot, friends and colleagues are being arrested and you are forced to sleep in safe houses.

The first images I remember seeing of Myanmar were at my grandmother’s house. Disintegrating home video reels and grainy black and white photos showed my father as a smiling toddler in a tropical garden. Originally from the United Kingdom, they had moved there from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) to work in the oil industry in the 1960s, when the country was known as Burma. I imagined it to be a romantic and magical place. It was years until I learned of the tragic history that unfurled after they were forced to leave.

When my flight touched down in Yangon on my first official visit to Myanmar in 2012, I was amazed by how familiar the country looked. It seemed little had changed since those old videos were filmed. Men and women still wore traditional dress and carried tiffin jars and umbrellas, girls in green school uniforms wore jasmine flowers in their hair, ox carts and barefooted monks in maroon robes lined the unpaved roads. Myanmar felt like a country frozen in time. In the 50 years since my grandparents left, Myanmar had been ruled by brutal military regimes, which had isolated the country and stalled development.

I was both nervous and excited to be in Yangon for the first time. For the past three years, I had been working at an exiled Burmese media organisation, the Democratic Voice of Burma, or DVB. The only contacts I had in the country were underground journalists who had spent years secretly recording and smuggling out footage so that DVB could broadcast uncensored content from its satellite channel.

When I met these brave journalists at a roadside stall, they spoke in hushed tones, warning me not to mention DVB. Myanmar was supposed to be undergoing a dramatic transition to democracy and I had travelled there to make a film about DVB journalists who had just been released from prison. But tensions were still high. People were reluctant to trust the military.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMyanmar’s parallel gov’t promises ‘revolution’ to reverse coup

Myanmar security forces kill dozens of anti-coup protesters

Myanmar court delays Suu Kyi’s hearing as more protesters killed

As the months rolled by and restrictions continued to ease, people started to relax, and after several months of going back and forth, I decided to make Myanmar my home. After years of house arrest, Aung San Suu Kyi ran for parliament and won, censorship was lifted, and foreign investment poured in. DVB was able to operate inside the country.

I worked as a freelancer for various local and international broadcasters, making documentaries and producing TV news about Myanmar and the region.

Then, in late January this year, I started hearing rumours of a possible coup. But no one I spoke to thought it would happen. The military had continued to act with impunity under a civilian government. It held key ministries, controlled the security forces and had secured its financial interests. A power grab would gain little and risk a lot.

On the morning of February 1, I woke early and glanced at my phone to see a dozen missed calls from the Al Jazeera newsroom. Then I saw the messages. “Aung San Suu Kyi has been detained” read the first one. As news came in of further arrests, it became clear that this was a military takeover.

It wasn’t long before the military began arresting my friends, colleagues and acquaintances. Many more are now in hiding.

As night settles over Yangon, a cloak of fear now comes with it. The 8pm curfew means streets are mostly empty but police use the cover of darkness to raid homes and offices and make arrests.

Late some nights, I hear my neighbours banging pots and pans – a practice that began as a show of protest but which is now also used to warn of approaching danger.

Every day I wake early, anxious to find out who has been arrested overnight.

As outrage turns to defiance, tens of thousands pour into the streets of Yangon to protest. Fears rise about how the military will respond. But when the crackdown comes, it is worse than I could have imagined. Security forces use live rounds and machine-gun fire, indiscriminately launching brutal attacks. Front-line medics, children, bystanders – no one, it seems, is safe.

A young friend phones to ask advice about filming with a phone. She grew up in Kachin state, a war-torn area of northern Myanmar, and knows more than most what the military is capable of. She tells me she was fleeing from the police when she hid in a stairwell. A police officer followed her inside and unleashed seven rounds of rubber bullets into her legs, hips and buttocks. I have seen the damage done by rubber bullets before. They cause gaping welts, dark bruising, broken skin and swelling, and can leave people incapacitated. I couldn’t begin to imagine the excruciating pain and damage they would have done at such close range to this slight young girl.

As the death toll rises, I am astounded by the resilience and creativity of those I know joining the protests, and the bravery of the local journalists covering it.

But as pressure builds, I see more friends and colleagues arrested. And fears for my own safety start to rise. There have been persistent rumours of a looming crackdown on foreign media. I receive phone calls from friends telling me to leave my home, so I sleep at safe houses. Then comes the news that the military government has not extended my visa.

Leaving at this critical moment in Myanmar’s history is not easy. Documenting what is unfolding feels more important now than ever. The heightened tension, lack of sleep and persistent anxiety have taken a toll. But for those who don’t have the option to leave – those who have lost loved ones, been arrested or are on the run – there is no respite in sight.

As the sounds of flash grenades and gunfire echo through Yangon’s townships, the state of fear has become ever present.

After I return to the UK, more bad news arrives: DVB and several other media organisations have been stripped of their licences, their offices raided and more journalists have been arrested. I feel tremendous fear and sadness for those I am leaving behind but I know they are determined not to back down or be silenced by this brutal regime.