The radio station at the heart of an India-GDR friendship

The untold story of a shared history is now coming to light.

Listen to this story:

Berlin, Germany – The 1980s represented a turbulent and transitional period in global affairs. The end of the Cold War was drawing closer, a new era of Thatcher-Reagan neoliberal economic politics was being ushered in, and India was reeling following the assassination in 1984 of its prime minister Indira Gandhi.

Keep reading

list of 3 items‘We’re afraid’: Far-right attack in Germany reignites fears

How did the fall of the Berlin Wall impact Germans of colour?

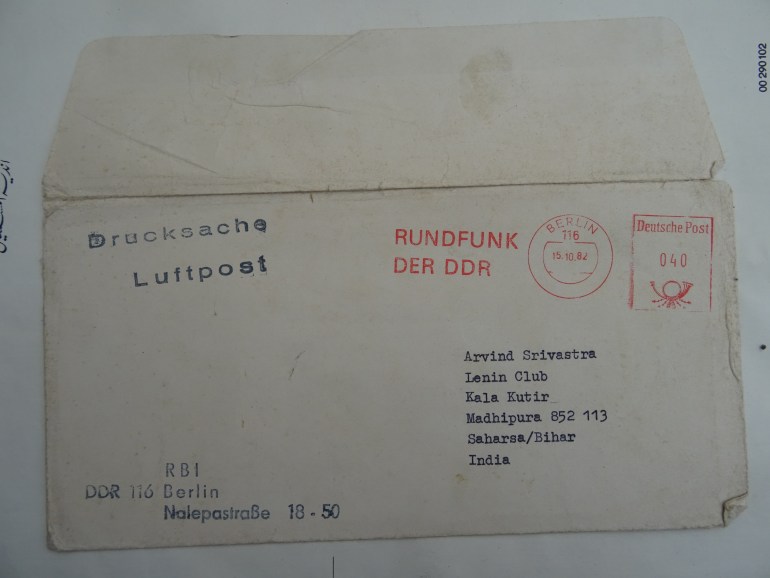

Keen to keep up with global current news and affairs, Arvind Srivastava, then a young student studying for a master’s degree in history in Madhepura, a town in the eastern Indian state of Bihar, would gather daily with a group of fellow students. Together, they would tune in to Radio Berlin International (RBI) and its Hindi-language socialist-tilting radio programmes.

From 1959 until German reunification in 1990, RBI served as the German Democratic Republic’s (GDR, or East Germany) international mouthpiece, transmitting news, views and values across the world through its multilingual broadcast platform.

For Srivastava, now 57, and a writer and poet, RBI played a pivotal role in illuminating his global vision during the Cold War.

“In the eighties, most of my friends and I were undergraduate or postgraduate students studying history and political science. In that era of information technology, radio was the only powerful medium,” he tells Al Jazeera.

“When the world was divided into two camps, by nature our country was very close to Soviet ideology. We were curious, and it was a matter of urgent pride for us to be part of the global mobilisation against imperialism, colonialism and racism.”

Srivastava founded the local listeners’ club, also known as a Lenin club, in Madhepura. The club was one of many across India’s Hindi-speaking regions including Punjab and Haryana in the north, Bihar in the east, and the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, where students and workers who shared the GDR’s political values listened to RBI together.

‘Entangled history’

But these listeners were more than just consumers of a state media mouthpiece. Their interactions with the Hindi-speaking East German moderators, which played out through correspondence and via the airwaves, led to them actively shaping what the station broadcast.

They represent what has been described by Indian researcher and academic Anandita Bajpai as the “truly entangled history of India-GDR relations” that still touches lives today, more than 30 years after RBI stopped airing.

“Even after so much time had passed, the fans still remembered the names of all the Hindi programme staff,” says Sabine Imhof, a former RBI editor who met fans in Haryana and Rajasthan a decade after the station’s closure.

“They invited me to their homes and showed me their collections of RBI souvenirs,” says Imhof, who was shown RBI plastic bags, posters, postcards and calendars. “RBI and the GDR have not been forgotten in India.”

Until recently, little was known about RBI and the relationships at its heart. But a new documentary and book, a collection of essays titled Cordial Cold War that explores the significant cultural links between India and the GDR edited by Bajpai, look set to change that.

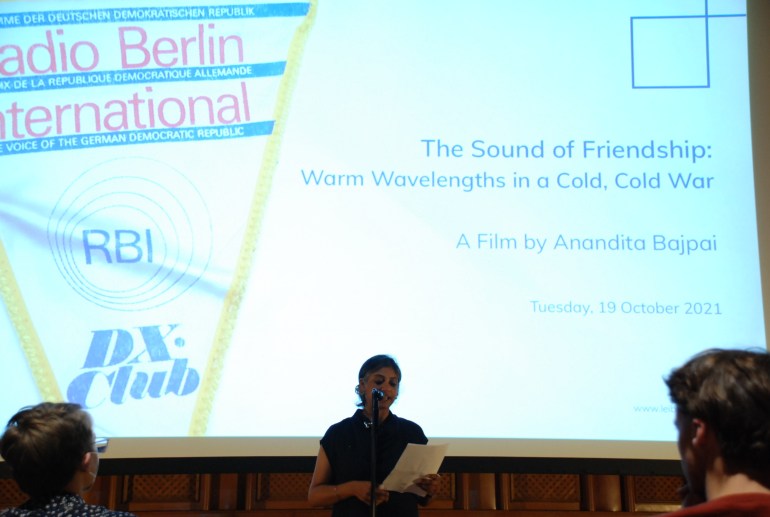

A research fellow at Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient in Berlin, Bajpai screened her film, The Sound of Friendship: Warm Wavelengths in a Cold, Cold War, in Berlin in October shedding light on stories which she says are usually found in the “footnotes” of history books.

A film at the Funkhaus

Nestled next to the tree-lined bank of the German capital’s River Spree and approximately 1km southeast of where the longest part of the Berlin Wall remains, sits the Funkhaus Berlin, an events venue popular among coworking space colleagues, cocktail drinkers and techno clubbers.

Yet during the days of the GDR, the Funkhaus served as East Germany’s main broadcast centre, a sprawling 135,000m2 space designed by a Bauhaus-schooled architect named Franz Ehrlich.

Built between 1952 and 1956 in the part of Berlin that was controlled by the Soviet Union during the years the city was divided between the Soviets and Western Allied forces, it once housed 5,000 employees. It featured a main broadcast hall and several studios that broadcast regionally and internationally to five continents, and in a number of languages including Kiswahili, Arabic, Spanish and English, according to Bajpai’s book.

Bajpai, speaking over a Zoom call, says although there was ample research on India-GDR relations over the past century, much of that stopped during the Cold War period.

Given these historical and archival gaps, she says a major aim of her work is to create a more holistic history.

“So much has happened to the way GDR’s history has been dealt with within the larger German context after reunification,” she says.

While Cold War historians have increasingly made efforts to give more voice to residents of the GDR, she says, “this smaller angle of India and GDR has all but disappeared”.

Now, a new perspective is emerging.

“What has been noticed by new Cold War history scholars in recent years is that there is a very particular kind of silence when it comes to voices from the Global South. Usually, in Cold War histories, actors from the Global South are projected as passive receivers of Cold War propaganda that stemmed from either of the two main blocs (the US and USSR),” she says.

“What the RBI story very beautifully shows is that actors from the South are anything but passive. In fact, they have contributed in so many vibrant ways, to even impacting the very making of radio as a medium.”

Rural radio listeners

Bajpai’s work highlights how RBI slotted into a radio landscape – the primary medium for many across the world at the time – alongside other state broadcast mouthpieces such as the BBC, Voice of America (VOA), Radio Moscow and RBI’s West German counterpart Deutsche Welle.

Yet, it was RBI that stood out among this particular Indian demographic.

It did not come from the United States or USSR, the major power blocs at the time, and it had a unique listener-radio station dynamic that veered away from other templates, such as the BBC’s coloniser-to-colonised format. “The relationship was not monolithic and unilinear. It was rather a mutually constituted one,” Bajpai says.

Bajpai, who has been researching India-GDR relations since 2015, first came across the RBI’s Hindi Division once she started looking into RBI’s general history three years ago.

As part of RBI’s South East Asian Department, which had been operating since 1959 and airing English-language news and features that appealed to India’s more urban listener, the Hindi Division first started airing from 1967 onwards and, as Bajpai discovered, quickly emerged as a favourite among Indians in more rural and semi-urban settings.

“What I found were the many listeners in India who were writing to the programme regularly, in some cases four times a week, and listeners’ clubs in their hundreds, particularly from rural and semi-urban places in India. In fact, the Hindi Division was one of the most popular ones of RBI,” she adds.

Fan mail

The division offered a diverse set of programmes and one main broadcast a day that was repeated four times in 24 hours. Alongside current affairs and sports news and views, there was a strong emphasis on sharing what life was like in the GDR, including a programme called GDR Darshan (a view into the GDR), while other regular features such as Kadam Badhao Aman Ki Khatir (take a step forward towards peace) reflected the GDR’s anti-fascist, anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist ideologies.

“RBI’s broadcasts were the voice of marginalised people, presenting the analysis of new developments with a new language in a very interesting and intuitive way,” says Srivastava. He recalls how for him and other listener club members, RBI made events in Nicaragua, Angola and Palestine and issues such as nuclear disarmament easy to understand.

The fans would write in with letters that, Bajpai discovered, were often lengthy and covered a range of topics with opinions on global affairs and politics, and questions posed about everyday life in the GDR, ranging from healthcare, travel and legal queries to income levels and favourite singers. There also was a lot of interest in family relationships, for example, on divorces and dowries, whether arranged marriages happened and what kind of gender roles existed.

Bajpai also began meeting former hosts in Berlin, who shared their private collections of memorabilia from the time that included fan letters, offers of marriage, poems and photos.

The department prioritised their listeners with fan letters addressed in regular features such as Aapki Chitthi Mili (we have received your mail), Aapne Poocha Hai (you have asked us), and Naye Mitron Ke Patr (letters from our new friends).

The letters and photographs that were regularly sent highlighted the various activities such as discussions, exhibitions and tea parties that club members held to show their support for the GDR’s values.

Unlike other radio networks who employed native speakers, RBI’s broadcasts on and from another country were told by locals who spoke the language of the listener. This held major appeal for Indian audiences and amazed them, according to Ujjwal Bhattacharya, a former RBI journalist quoted in the book, and who was among a minority of Indian journalists when the majority of Hindi-speaking hosts were from the GDR.

Despite there being incomplete archive material from the Hindi Division, Bajpai unearthed 200 recorded magnetic tapes that aired between September 1989 and October 1990, and records that noted each department’s fan mail statistics.

Deep love for RBI

Bajpai used Facebook to track down Srivastava, armed only with the knowledge that he was a poet and in the hopes that he may have posted something about RBI. She found him in 2018 and meetings in India followed.

“The idea of the film came because of him,” she says. “Whenever I spoke to him, he expressed such intense love for the people at RBI to the extent that he knew all their names, their voices.”

Bajpai says she thought the film could facilitate a meeting between Srivastava and those he calls his mentors.

Thirty-plus years on, Srivastava continues to see the effect and relevance of RBI as imparting a global perspective. “The generations that follow can learn a lot from the India-GDR friendship,” he says.

“India’s agricultural, technical and technological ties with GDR, as well as GDR’s intense participation in international sports, deeply impressed us, and the efforts of the Indo-GDR friendship for world peace, sovereignty and equality can never be forgotten. It is like medicine for the coming generation.”

The film, at just over an hour long, takes us on a journey from Berlin to Bihar and back, placing Srivastava at the centre of the story. We learn about his discovery, interest and continuing enthusiasm for the station and what it stood for, and also hear from former listener club members and former hosts about the history and friendships they shared.

Bajpai says she was overwhelmed when she saw how much memorabilia Srivastava still had.

“What I find fascinating is how these things, which probably did not have such value within the GDR, were valued so much by Indian listeners. They almost served as that very important material link between presenters and listeners. Everything that travelled to Madhepura has been kept alive in that attic,” she says, referring, for example, to a cap that listener club members wore to the cricket or while listening to RBI.

In a TV and digital-free era where radio was the main means of connecting with the world, RBI souvenirs like posters, stickers and books held elevated symbolic value, according to Srivastava. “We considered it our moral responsibility to preserve the materials sent by RBI.”

As Bajpai discovered, for the East Germans, working in the division gave them the opportunity to develop connections with people from a country they had studied, and practise the Hindi they had learned at the Humboldt University in East Berlin.

Imhof, now a faculty member in the Humboldt University’s Language, Literature and Humanities department worked at the radio station as an editor between 1983 and 1990. She says her time at the station showed how similar Indians and East Germans were. “The links might be down to people in the GDR being more social, and not as egoistic or self-conscious,” she says. “A sense of community was more important than private property and becoming rich.”

Bridge between past and present

German reunification in 1990 led to the closure of the station with it being absorbed under its West German counterpart Deutsche Welle as the country’s main international broadcaster that remains on air today.

The station’s closure was a sad moment for both RBI’s staff and listeners, a sentiment that was shared at the private screening at the Funkhaus.

Screened in front of more than 100 people, the crowd included a number of people from RBI’s past, including former RBI director Klaus Fischer.

At a reunion of sorts for former employees in their former workplace, the story’s protagonists spoke about how good it was to see this history finally being told.

“When I visited India after the station’s closure, former fans said that while they were all happy about German unification, they missed RBI. This, alongside now with the film, illustrates the importance of RBI, the long lasting, personal relationship between journalists and listeners,” says Imhof, who found the reunion an emotional experience. “It also shows how we still share the same human ideas and the feeling of one community.”

There are plans, pandemic permitting, to take the film across Germany and India. The film has since been dedicated to Srivastava’s wife Poonam Lata Sinha and father Harishankar Srivastava “Shalabh”, who both passed away from COVID after the film was made.

Going forward, Bajpai says she will continue to work on furthering the oral, visual and written archive on the cultural links that remain untold.

“What I find more sort of striking about these stories, is that at the end of the day, it’s about individual and collective human recognition. A lot of the people from that time have felt that their voices have disappeared and I think this kind of research places them back on the map in more ways than one,” she says.

Back in Madhepura, Srivastava continues to use his role to raise awareness about the shared history, having recently overseen an exhibition of memorabilia in his hometown that is due to be shown again next year.

“The roots of Indo-German friendship are very deep and spread across the fields of education, literature and research. The film can play an important role in giving new heights to the relations between our two nations and is a bridge between the past and the present,” he says. “It is a strong start, but there is still much of this historical narrative yet to be told.”