China’s history wars: Controlling present, past and future

Since the formation of the People’s Republic of China, the Communist Party has sought to control China’s tumultuous history.

Hong Kong, China – Since crushing the Nationalists in China’s civil war in 1949, the ruling Communist Party has been the author, and mythmaker, of the country’s modern history.

It is the Propaganda Department’s job to ensure the party’s version of history is enforced, supported by so-called “patriotic education”, which now expands into areas well beyond the classroom. It is also being extended to Hong Kong, a once-thriving marketplace for duelling versions of modern China’s history.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsChina’s Communist Party at 100: Where are the women?

‘No more couching party leadership in terms fuzzy and warm’

Infographic: 100 years of China’s Communist Party

“The Party treats history as an issue of political management in which the preservation of the Party’s prestige and power is paramount,” wrote author Richard McGregor in his book, The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers.

Early in his first term, China’s president and Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping declared war on “historical nihilism”, which he defined as any attempt to challenge the official narrative of significant past events.

On Thursday, as the party celebrated its 100th birthday, Xi again reminded the crowds in Beijing of the importance of history.

“Through the mirror of history we gain a foresight into the future,” he said. “We can see why we were successful in the past and why we will continue to succeed in the future.”

One of the party’s founding principles was “upholding truth”, he stressed.

Xi “knows well that one who controls the present should control the past,” said Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at SOAS at the University of London. “If Xi and the Party can continue to do so, they believe they can determine China’s future, and people in China will embrace it, as whatever Xi wants for China is ’the will of history’.”

Here are four groundbreaking moments from Chinese history during the Communist Party’s first century that underline the gulf between official and public accounts:

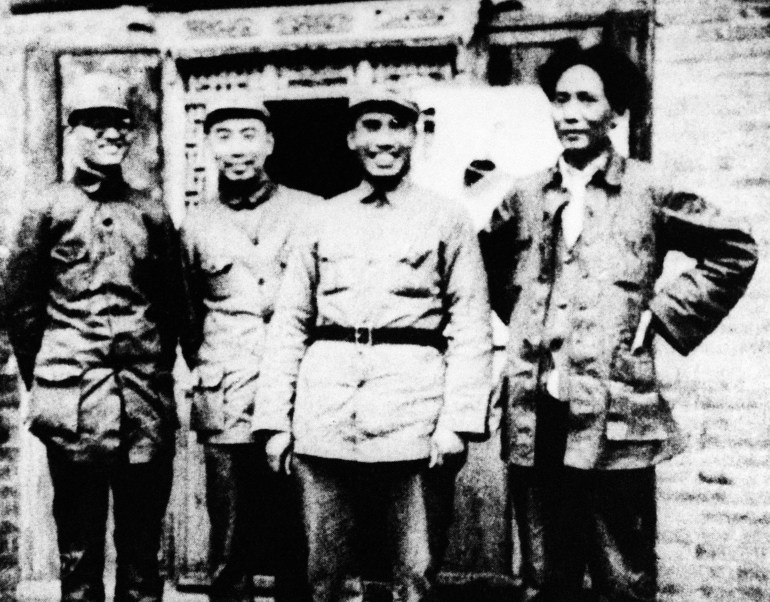

The Long March (1934-1936)

CCP version: An epic military manoeuvre led by brilliant strategist Mao Zedong to outrun encircling Nationalist troops in what has become the People’s Republic’s founding myth. Mao’s Red Army – numbering about 80,000 people at the beginning – trekked about 12,500 km (7,800 miles) across vast tracts of the country from coastal Jiangxi Province to establish a new base in mountainous northwestern China. Along the way, Mao’s heroic soldiers attracted the support of “ordinary” people and overcame enormous challenges.

What the CCP didn’t say: The retreat had a disastrous first few months and was ambushed by the Nationalists early on at the cost of between 15,000 and 40,000 lives. Mao was able to sideline another, Soviet-backed faction within the party and emerge as the undisputed leader of the Communist forces. The dwindling troops sometimes resorted to kidnapping – and tortured and executed those they took captive as “class enemies”.

Great Leap Forward (1958 – 1962)

CCP version: Great Helmsman Mao’s revolutionary programme to accelerate industralisation in order to beat arch enemies and advanced economies such as the United Kingdom and the United States. The entire population followed the thrust of Mao’s Thought and adopted a newly invented method of organisation – the commune – to dramatically boost industrial output overnight. It is officially referred to as a “difficult period lasting three years”, according to The Party author McGregor.

What the CCP didn’t say: Overzealous cadres executed the programme in great haste and made mistakes that snowballed into calamities and led to the deaths of between 35 and 40 million people, according to former Xinhua news agency journalist Yang Jisheng who documented the tragedy in his book, Tombstone. The utopian communes proved to be inefficient and the large-scale diversion of farm labour into small-scale industry undermined food production. Compounded by a slew of natural disasters and the Soviets’ withdrawal of support, the programme resulted not in “true communism” but the worst man-made famine in history.

Cultural Revolution (1966-1976)

CCP version: Mao’s last-ditch bid to fight a conspiracy by pro-capitalists among the ranks of Communist Party leadership and prevent the party from going astray. Deng Xiaoping, who was purged but emerged after Mao’s death in 1976 as the country’s paramount leader, declared the episode a decade-long calamity. Blame, however, lies squarely at the feet of Mao’s hand-picked successor Lin Biao, who died in a plane crash during his escape to Mongolia, and the Gang of Four, which included Mao’s widow and longtime revolutionary companion Jiang Qing, was put on a televised show trial.

What the CCP didn’t say: The campaign was orchestrated by Mao to purge his political enemies, real or perceived, and re-impose strongman rule. Driven by idolatry for Mao, mobs of teenagers and young people joined the Red Guards and threw themselves into a crazed and violent campaign against the perceived enemies of Mao and the party. In colleges and high schools throughout the country, they repudiated their teachers and principals as “capitalists” or “stinking intellectuals” in so-called struggle sessions, children turned against parents and different factions within the party denounced each other. There were public beatings and mob violence, and even cannibalism. Historians believe as many as two million people died in the chaos.

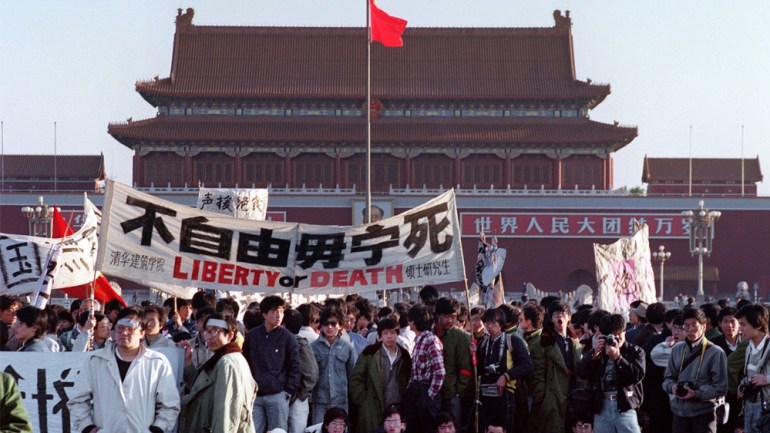

Tiananmen Square (1989)

CCP version: In a 90,000-character chronicle of the Party’s first 100 years released last month, the incident was characterised as “certain political disturbances that erupted in Beijing and a few other cities as part of an anti-revolutionary riot… The riot was suppressed to make way for continuous reform, opening up and modernisation.” Authorities say no one was killed on Tiananmen Square, where demonstrators had gathered in the tens of thousands when the tanks rolled in and soldiers armed with bayonets and rifles were deployed to demolish the six-week-long encampments.

What the CCP didn’t say: Tiananmen Square was an anti-corruption and pro-democracy movement led by university students in the capital and joined by fellow citizens from more than 400 cities across the country, and was sparked by the death of the deposed reformist leader Hu Yaobang. Analysts estimate the troops of the People’s Liberation Army killed several hundred to several thousand demonstrators and wounded thousands more as they cleared the square.

Al Jazeera’s Adrian Brown, who is now based in Hong Kong, was there. “I saw a lot that day that I will never forget,” he wrote in 2019 on the 30th anniversary of the crackdown. “A tank treading on two flattened bodies, a burned-out army personnel carrier and the charred corpse of a soldier inside.” Wu’er Kaixi, one of the student leaders who famously confronted Premier Li Peng while in his hospital gown, said the protesters simply wanted democracy. “We expected some bloodshed, to be hit by police batons, perhaps. That’s what we had expected,” he said. “Live ammunition? No. Never.”

Mi Ling Tsui of Human Rights in China says Tiananmen has become a subject of “enforced amnesia“.

With reporting by Violet Law in Hong Kong