Ukraine faces enormous military odds against Russia

But Russia – and many experts – insist an armed invasion is not the intention.

Athens, Greece – As the United States and NATO refused concessions on Russia’s key security demands, the Russian and Ukrainian militaries remained arrayed across a long common border.

The US has demanded Russia withdraw its troops for talks to continue, but those forces represent one of Russia’s key advantages in the standoff.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsLatest Ukraine updates: US formally responds to Russia’s demands

Can war in Ukraine be averted?

The national balance of forces is overwhelmingly in Russia’s favour.

Russian military spending in 2020 amounted to $61.7bn in 2020; Ukraine’s was less than a 10th of that at $5.9bn, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

And the Red Army counts 900,000 men under arms, compared with 209,000 in the Ukrainian Army, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies. This means Russia can more easily rotate fresh troops into a prolonged conflict.

While NATO members this week ordered planes and ships to reinforce alliance members in Eastern Europe, none has pledged troops to Ukraine.

Russia is believed to have mobilised 100,000 soldiers to the north, east and south of Ukraine, but the key Russian advantage, analysts say, may be in the air.

“The residual weight of Russia’s armed forces not deployed at its borders, in some cases [can] be deployed quite rapidly, and I’m specifically thinking of airpower and ballistic missiles,” said Samir Puri, a senior fellow at the IISS.

Russia is also at a more advanced state of preparedness for armed conflict than Ukraine, having begun mobilisation of troops last November.

Russia has a third advantage. It has sympathetic special forces already fighting the Ukrainian military in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions, reporting on Ukrainian tactics and capabilities, and able to connect to Russian forces in an invasion scenario.

Puri believes politics may be a fourth Russian advantage.

“Ukrainian politics is quite a fractious sport because it’s undergoing a period of protracted reform from an oligarchical system. Russia is ruled under the iron grip of the regime and there wouldn’t be any vacillation on the Russian side,” he said, calling any Russian-Ukrainian war “an unfair fight”.

“There are people with very different memories of the USSR and very different understandings of what Ukraine should be in the future,” added Puri, who spent a year in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region in 2014-15.

NATO’s response

The scale of NATO’s response does not suggest it believes a war is imminent.

On Monday, NATO said it was putting its forces on standby and reinforcing Eastern Europe with troops, ships and fighter jets.

Russia, which claims it has no intention of invading Ukraine, said the move amounted to “hysteria”.

NATO has 40,000-strong response forces across Europe. The most combat-ready part of this is the 5,000-strong, French-led Very High Readiness Joint Task Force, containing air, land and sea elements that can be operational within 72 hours.

NATO has 4,000-strong forces in Romania, which France this week offered to reinforce. Spain offered to sent naval and troop reinforcements to Bulgaria, though the government in Sofia has for the moment rejected them.

NATO also has four multinational battalions stationed in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland, numbering 4,000 men in total, equipped with tanks, air defences and intelligence units.

The US, which has 74,000 military personnel in Europe including active-duty soldiers, said this week it would put 8,500 men on high alert.

What does Russia want?

Ostensibly, Russia is concerned with security.

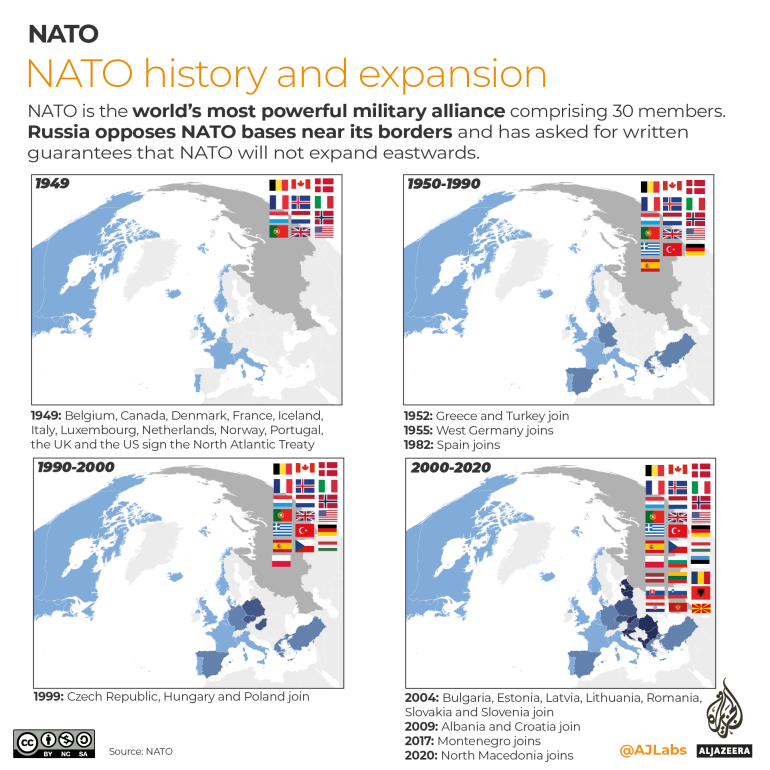

In December, it sent the US two draft security treaties that would halt NATO expansion in Eastern Europe and withdraw all NATO assets from former Warsaw Pact countries. The US and NATO on Wednesday rejected those demands.

There is also Russian President Vladimir Putin’s growing revisionism.

In an essay last July, he decried both the artificial splintering of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine – parts of a single nation in his view – and of the USSR in 1991.

The right of republics to secede, written in the USSR’s 1924 constitution, he wrote, “planted in the foundation of our statehood the most dangerous time bomb, which exploded the moment the safety mechanism provided by the leading role of the [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] was gone, the party itself collapsing from within. A ‘parade of sovereignties’ followed.”

Yet, Putin’s third concern is securing the uninterrupted export of Russian natural gas, which covers more than a third of Europe’s needs.

On a technicality, Germany has delayed the operation of Nord Stream 2, a Russian-built pipeline that would export 55 billion cubic metres of gas a year to Western Europe.

A carefully engineered crisis

Experts differ on how serious is the prospect of a Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The IISS’s Nigel Gould-Davies argued in the Moscow Times that Russia’s “immediate concern is not the 25-year history of NATO enlargement, but its own currently declining influence over Ukraine – whose Western ties are growing deeper, resistance to local pro-Russian figures like Viktor Medvedchuk sterner, and national identity stronger”.

“Since time is not on Putin’s side, he is seeking to assert dominance over Kyiv while this is still possible,” Gould-Davies said.

The time pressure suggests that if any Russian aggression is to come, it will come sooner rather than later. But this would likely be a double-edged sword, strengthening NATO’s presence in Eastern Europe.

NATO stationed multinational forces in its Eastern European members only after the 2014 Ukraine crisis, in which Russia occupied the Crimean Peninsula.

Not all NATO members are convinced that an invasion is likely. Germany, for example, has refused to sell Ukraine surplus military stock, preferring to take a diplomatic approach.

“The fact is, the whole invasion threat could be a bluff,” Puri said.

“In that case, you can imagine in a couple of months, when the weather changes and a tank invasion is a lot less likely because it becomes a lot more boggy as the ice melts, the Russians would be laughing to themselves that London and Washington got themselves into such a fevered state over this, and Germany may be thinking, ‘we made the right decisions and re-engaged with Russia on a dialogue basis’.”

A pullback would still leave Russia with the advantage of dramatically raising the issue of NATO expansion in the public consciousness, said Puri.

“Many educated people and those who don’t have an axe to grind on this might actually interrogate the potential for NATO expansion to create greater insecurity,” he said.

“They may not agree with Russia, but they might decide that NATO expansion is a bad idea. That’s actually quite a gain from Russia’s perspective.”