Ukraine war: Why is Roman Abramovich trying to broker peace?

The Russian billionaire’s role at negotiations surprised some, but observers say Abramovich is a skilled middleman.

Roman Abramovich is one of the most eccentric post-Soviet oligarchs who hardly looks fit to be a peace negotiator in the Russian-Ukrainian war.

The 55-year-old billionaire with carefully maintained stubble is known as a recluse who barely makes eye contact in conversation.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhat compromises will Russia and Ukraine make to end the war?

‘Not naive’: Ukraine questions Russian pledge to reduce attacks

Putin’s philosophers: Who inspired him to invade Ukraine?

Abramovich made his riches during Russia’s transition to capitalism in the 1990s – and wielded enormous power behind the Kremlin throne of Boris Yeltsin, Russia’s first post-Soviet president who handpicked Vladimir Putin as his prime minister and successor in 2000.

During Putin’s first terms, Abramovich governed Chukotka, a permafrost-covered Siberian region whose entire population of less than 50,000 could easily fit in one of the stadiums where Chelsea, the Premier League football club he bought in 2003, played.

Abramovich decided to sell the club earlier this month before London and the European Union sanctioned him and froze his assets for his “privileged access” to Russian President Vladimir Putin that helped him “maintain his “considerable wealth.”

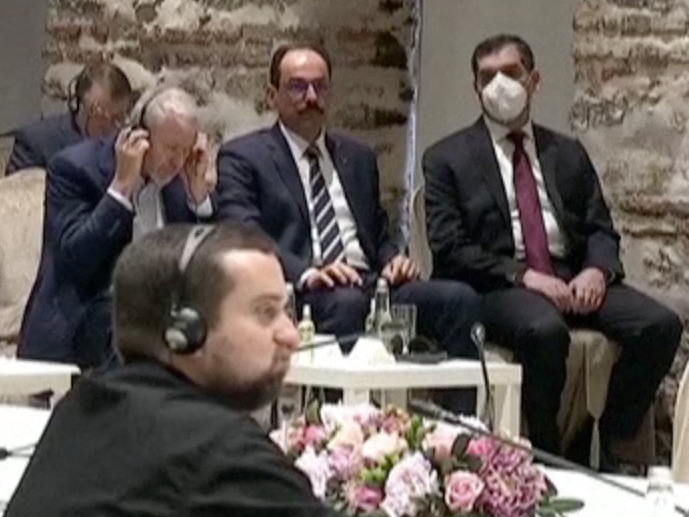

On Tuesday, Abramovich was seen taking part in peace talks between Moscow and Kyiv, more than a month after Russia invaded Ukraine, in Istanbul, where he met with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

That meeting came days after unverified claims of his poisoning. According to the Wall Street Journal, Abramovich and at least two senior members of the Ukrainian team were allegedly poisoned – and had red eyes, constant and painful tearing, and peeling skin on their faces and hands. However, that claim was quickly refuted by United States and Ukrainian officials.

On his role as a broker, Gennady Gudkov, an exiled Russian opposition leader who served three terms in the State Duma, Russia’s lower house of parliament, told Al Jazeera: “He has a fantastic flair for seeing the future, he has a very special ability to predict it.”

Ukraine also reportedly has a positive view of Abramovich.

The Wall Street Journal reported on March 23 that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy specifically asked his US counterpart Joe Biden not to add Abramovich to a list of sanctioned Russian oligarchs because he “might prove important as a go-between with Russia in helping to negotiate peace.”

The newspaper cited “people with knowledge” of the Zelenskyy-Biden phone call that took place in early March.

Zelenskyy’s press service was not immediately available to comment on Abramovich’s participation in the talks.

While Ukraine’s leader may understand his role, some are yet baffled by his appearance at talks.

“This is a complete surprise. I don’t even know what to say,” a politician with Zelenskyy’s Servant of the People party told Al Jazeera.

The answer may lie in the decision he made in the late 2000s when his tenure as Chukotka’s governor ended.

Abramovich opted to dissociate himself from the Kremlin and a handful of billionaires who remained in Russia and got involved in Putin’s economic projects to transform the economy through stricter government control.

“He is not deeply integrated in Putin’s political actions. He distanced himself from other Russian oligarchs, tried to make a name and an image for himself abroad,” Gudkov said.

Even though the efforts did not thwart the sanctions, they helped him to be seen as a figure trusted by both sides.

“Abramovich is a bridge between Western and Russian elites,” Aleksey Kushch, a Kyiv-based analyst, told Al Jazeera.

He said that other Russian oligarchs – including those who are either Westernised or nationalist, conservative “nativists” – are distrusted by either Russia or Ukraine.

But “Abramovich suits everyone,” Kushch said.

Even his longtime political foes admit his ability to navigate his way in the most complicated negotiations.

”What makes him interesting is his talent to organise shadowy financial schemes,” Alexander Korzhakov, President Yeltsin’s former security chief who was at odds with Abramovich in the late 1990s, told this reporter in 2018.

“But among businessmen, Abramovich has always been respected – he kept his word and never robbed anyone,” Korzhakov said.

While known for his middleman skills, his personal history is of great tragedy and success. His maternal grandparents were Jews who fled Soviet Ukraine to Russia during World War II, but both died by the time he was three.

As a teenager, he was a street vendor of plastic toys in Moscow and went on to become one of Russia’s richest men with interests in oil.

He maintained ties with Ukrainian Jewish businessmen – and can relate to President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who hails from a Russian-speaking Jewish family.

However, at least one of his deals with Ukrainian businessmen went terribly wrong – so wrong that no other than Putin mentioned it.

The Russian president claimed in 2014 that Ukrainian oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky “scammed” Abramovich “two or three years ago”.

“They signed some deal, Abramovich transferred several billion dollars, while this guy never delivered and pocketed the money,” Putin told a news conference. “I do not know, by the way, if he ever got his money back and if the deal was closed.”

The Ukrainian Anticor publication that specialises in reporting corruption claimed that the deal Putin referred to was Abramovich’s attempt to buy five plants from Kolomoisky in 2007.

Zelenskyy, who was one of Ukraine’s most successful comedians and television producers before his meteoric rise to the halls of power, was also closely tied to Kolomoisky.

For years, his District 95 comic troupe ran a television show on a television channel Kolomoisky controlled, and Zelenskyy’s presidential campaign was widely supported by all media outlets friendly to Kolomoisky.

The two, however, had a gradual falling out – something that helped Zelenskyy boost his rating as an anti-corruption champion.