Kharkiv triumph raises Ukrainian spirits – and victory hopes

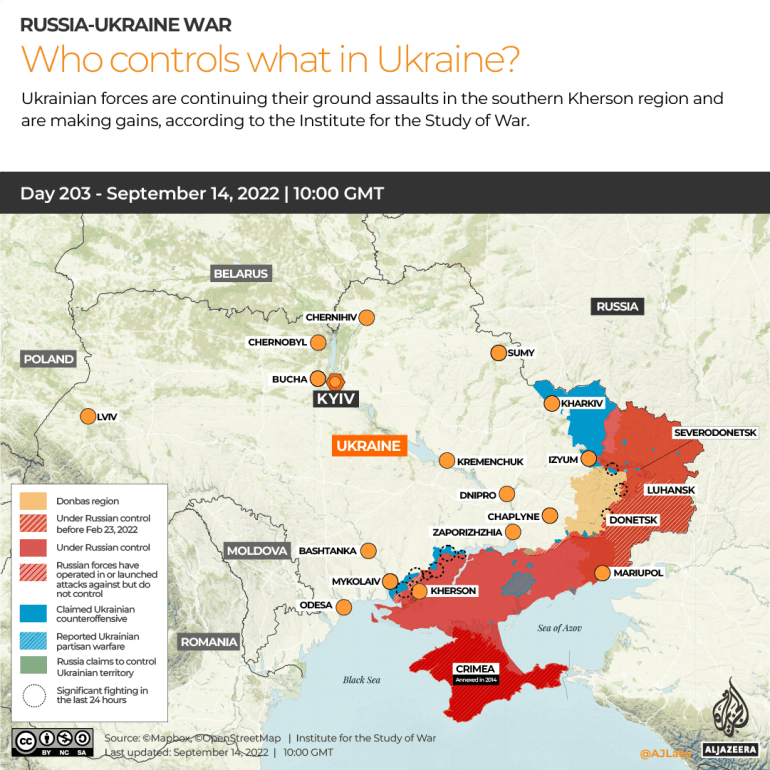

Ukraine has reclaimed 8,000 square kilometres of territory this month inflicting serious blow to Russian military ambitions.

Ukraine has won a decisive victory in the 29th week of the war, reclaiming an estimated 8,000 square kilometres (3,090 square miles) of northeastern territory from Russian forces, inflicting a serious blow to Russian morale and convincing their Western allies that Kyiv could defeat Moscow.

The recent battlefield successes also suggest that Kyiv’s goal of re-establishing the country’s 2014 borders may be achievable. Ukraine has pledged to regain control of Crimea Peninsula annexed by Russia in 2014.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUkraine reclaims more territory from Russia in counteroffensive

Ukraine’s counteroffensive explained in maps

As Ukraine advances, cracks begin to appear in Russia’s media

“The entire Donetsk region will be liberated,” predicted Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy as his forces stood poised to take the strategic town of Izyum, suggesting Ukrainian forces will soon press their advantage east.

But US President Joe Biden warned against great expectations, saying the war would be “a long haul”. Still, Ukraine may have turned a corner in procuring weapons it says it desperately needs.

German daily Suddeutsche Zeitung said the US is now considering sending to Ukraine the Western main battle tanks and infantry fighting vehicles it has been crying out for.

In an interview with Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz did not rule out sending his country’s heaviest tank, the Leopard 2, to Ukraine saying, “we will … coordinate closely with our allies. The situation is dynamic.”

Ukraine’s counteroffensive in the northern Kharkiv region began on September 6, even as another counteroffensive in the south begun a week earlier continued to unfold.

On September 8, Ukrainian forces took Balakliia, their first major prize, and came within 15km (9 miles) of the key logistics hub of Kupiansk. Lieutenant General Oleksiy Gromov said Ukraine’s counteroffensive had advanced to a depth of 50km (31 miles) behind enemy lines, reclaimed 700sq km (435sq miles) and secured 20 settlements.

The counteroffensive picked up speed the following day, liberating 30 settlements and 1,000sq km (621sq miles). Moscow-installed administrator for Kharkiv, Vitaly Ganchev, admitted that Kyiv had scored a “substantial victory”.

Russia’s defence ministry announced it was rushing reinforcements to the area, as it was caught off-guard by the Ukrainian push. It released video of a convoy of vehicles setting out from Raihorodka in Luhansk region – south of Kharkiv.

But it was too little, too late.

On September 10, Ukrainian forces recaptured the western half of Kupiansk, which lies astride the Oskil river, and advanced south along the river to reach the outskirts of Izyum, which they recaptured the following day.

At its northern extreme, the counteroffensive marched to the Russian border, taking Vovchansk, north of Kharkiv city.

Ukraine recaptured 20 settlements on September 12, re-establishing control as far north as Ternova on the Russian border and as far east as Dvorchina on the west bank of the Oskil river.

Moscow: It’s all part of the plan

Although the Kremlin admitted defeat on September 13, it originally claimed it was tactically retreating from the area west of the Oskil river, which now forms the new front line.

Some observers told Al Jazeera the Russians did indeed plan a tactical retreat, aware of a coming counteroffensive. Yet there is more evidence pointing to a rout.

Soldiers of the 1st Motor Rifle Regiment based in Izyum wrote en masse to their commander on August 30 asking for leave, suggesting they knew of the coming battle. Leave would have been unnecessary in a planned withdrawal.

Ukraine put Russian fatalities on September 6, the first day of its Kharkiv counteroffensive, at 460. On day two, it estimated Russian fatalities at 640, and 650 on day three.

To put these figures in context – during summer, Ukraine estimated Russian fatalities at 150-200 soldiers a day. After August 24, as Ukraine’s counteroffensive in the south built up with artillery followed by a ground offensive on August 29, those estimates rose to 300-450 dead. The losses in Kharkiv may be the highest daily tolls of the war for Russia.

There was further evidence of a disorganised retreat. Ukraine’s general staff said Russian forces were stealing civilian vehicles to escape. It said about 150 soldiers “departed Borscheva and Artemivka on two buses, one truck and 19 stolen cars,” on September 11. Another Russian unit left Svatove in Luhansk oblast by stealing more than 20 cars from locals, the staff said.

Ukraine’s military intelligence intercepted phone calls of the 202nd motorised rifle regiment while in retreat from Kharkiv. Left without communications and commanders, they asked relatives in Russia to contact the defence ministry hotline in Moscow to ask for instructions or extraction. Half the regiment was captured.

Russia said its tactical retreat meant to prioritise the fight for Donetsk region in the east, but Ukraine’s advance to the Oskil now exposes all that Russia has gained in Luhansk and Donetsk to an attack from the north.

Russian forces doggedly continued their offensives to capture Bakhmut, a communications node in Donetsk, even as Kiyv’s forces advanced to their north.

“Even the Russian seizure of Bakhmut … would no longer support any larger effort to accomplish the original objectives of this phase of the campaign, since it would not be supported by an advance from Izyum in the north,” said the Institute for the Study of War.

“The continued Russian offensive operations against Bakhmut and around Donetsk City have thus lost any real operational significance for Moscow.”

The Kharkiv offensive may have triggered desertions behind the front lines. Ukraine says Russian servicemen fled Svatove, 40km (25 miles) east of the Oskil river, leaving only local Luhansk militiamen to defend it.

In the southern Kherson region, satellite images showed all except four vehicles absent at the Russian base in Kyselivka, suggesting that the Donetsk People’s Republic unit that manned it may have fled. And reports surfaced that Russian troops were abandoning Melitopol in the heart of Russian-occupied Zaporizhia region, and retreating to Crimea.

Such desertions are encouraging partisans to mobilise. Luhansk governor Serhiy Haidai said Ukrainian partisans had retaken Kreminna, 12km (seven miles) behind enemy lines, and raised the flag there on September 11. Russian troops and collaborators were heading for the border, he said.

Ukraine’s southern counteroffensive also remained active during the Kharkiv operations. The Kakovka operational group reported 500sq km (193sq miles) of Russian-occupied territory have been reclaimed this month, and 13 settlements recaptured. Ukrainian forces have advanced between 4km (2.5 miles) and 12km (seven miles) in various places along the front. “But the invaders still have a lot of strength and capacity,” the group said.

Ukrainian victories have disrupted Russian recruitment, said Ukraine’s general staff. “The current situation in the military theatre and distrust for top command has forced a large number of volunteers to abandon the prospect of combat service,” the staff said.

Russian politics still in Putin’s thrall

Will there be political repercussions for Russian President Vladimir Putin?

Going by the results of the local and regional elections held on September 11, Putin still wields influence, as his supporters scored an overwhelming victory. But this is part of a waiting game by an opposition that sensed this was not its moment to strike, Russia observers have said.

“The number of candidates was the lowest for the last 10 years,” said Stanislav Andreychuk, co-chairman of Golos, Russia’s largest independent election monitor. “Very bright, very strong candidates didn’t take part in elections because political parties didn’t move them [towards elections]. Sometimes, they even cleaned them from their membership lists.”

Opposition parties have opted to keep their powder dry for now, said Andreychuk. “The main political topic all over the country is war and sanctions. But you can’t really talk about it in public, especially if you are against, because you can get seven or even 10 years in jail. So candidates tried to be very, very careful.”

Yet avoiding the elephant in the room was such a conscious exercise, said Andreychuk, it may even have emphasised Putin’s current political fragility.

“Everybody understands that everything can be changed immediately,” he said.