Could Venezuela’s diaspora hold the key to its opposition primary race?

With 7.7 million people who recently fled abroad, Venezuela’s opposition hopes the diaspora could turn into a political force.

Bogota, Colombia – Ever since Gisela Serrano fled Venezuela in 2018, the 53-year-old has felt like she has one foot in her adopted home of Colombia and another in her native country, where she hopes to one day return.

For that to happen, though, the country’s humanitarian crisis would need to improve. So Serrano, a migrant rights activist, follows the political situation in Venezuela closely.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsWhy are Venezuelan refugees disappearing in Colombia?

Mass arrest at LGBTQ club in Venezuela prompts outcry over discrimination

But until recently, she has been unable to vote in Venezuelan elections. A migrant herself, she has no valid passport, and the Venezuelan embassy in Bogota, where she currently resides, had been shuttered until September.

“It’s unfair,” said Serrano. “You feel helpless, watching everything happening from afar.”

On Sunday, however, Serrano and thousands of other Venezuelans from the diaspora will vote for the first time in a presidential primary. In the independently organised election, voters will choose a single candidate to challenge President Nicolas Maduro in the 2024 general elections.

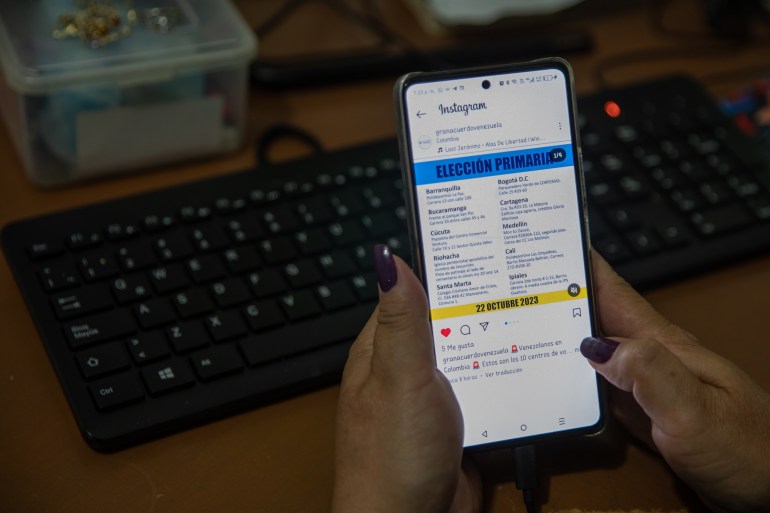

Organisers of the opposition primary have sought to widen out-of-country voting by allowing Venezuelans abroad who are listed in voter rolls to update their information and cast a ballot.

“We want to highlight that there are millions of Venezuelans abroad that are being denied their fundamental right to vote,” said Ismael Pérez, a member of the National Primary Commission (CP).

More than 7.7 million Venezuelans have left the country in recent years, fleeing political turmoil and an economic crisis spurred by government mismanagement, falling oil prices and United States sanctions.

Within that diaspora, 4.5 million Venezuelans could be eligible to vote, Perez said. That number could prove decisive in future elections.

In the lead-up to the October 22 primary, the CP paired with thousands of local volunteers to set up 80 polling sites across Latin America, Europe, the US, Canada and Israel.

It also held a months-long drive to update voting rolls for Venezuelans abroad, bringing the total number of migrants, asylum seekers and refugees eligible to cast a ballot up to 397,000.

That is a significant jump from the previous count of about 86,000 voters abroad, Perez said.

One of those voters is Serrano, who — despite having left Venezuela five years ago — is determined to help shape the future of her country. Before she migrated, she volunteered as an electoral observer and voted in every election since she turned 18.

But her commitment to free elections ultimately made it difficult for Serrano to stay in Venezuela.

In the 2017 regional vote, a local coordinator for the United Socialist Party of Venezuela warned Serrano that, if she returned to the polling station where she volunteered, she would not leave the site alive.

Fearing for her life, she escaped to neighbouring Colombia, where she was granted political asylum.

Her safety, however, came at the expense of her suffrage: From across the border, she could no longer vote.

“It’s the robbery of your freedom, of your right to express your approval or disapproval,” said Serrano of the elections.

While many diasporas are not politically active at a high rate, the Venezuelan diaspora could be an exception, according to Eugenio Martinez, a Venezuelan political analyst. After all, many fled the country due to political pressures.

“That this presidential election may serve to resolve the causes that forced them to leave the country is a more than sufficient reason to encourage voting,” said Martinez.

But Venezuelans abroad face a series of challenges to voting, starting with the fact that many are not registered in the official voting rolls overseen by the National Electoral Council.

Perez, the CP member, said the problem is made worse by the fraught diplomatic relations Venezuela has with many countries, which limits the number of Venezuelan embassies around the world.

Another issue is that Venezuelans must have permanent legal residence in their adopted country to vote, something many have yet to attain.

Jonathan Noguera, a refugee and migrant rights activist in Lima, Peru, also fears his fellow Venezuelans may be discouraged from voting in Sunday’s primary due to the fact that they are still unable to cast a ballot in the general elections.

“It’s a contradiction. They ask why they should vote in the primary if they can’t vote in the general election,” said Noguera.

Still, over the past week, Venezuela has taken some modest steps towards allowing a fair election in 2024.

On Tuesday, the Maduro government and the opposition signed a pledge allowing political parties to select their own candidates. Those candidates would have equal access to media coverage and international observers would be allowed to monitor the vote.

In exchange for the election concessions, the US agreed to ease some of its sanctions against Venezuela. But many advocates say the agreement did not go far enough.

Martinez argued that the terms for a free and fair election should include the right to vote for the diaspora, which represents about one-third of the total voting population.

“That such a significant number of people cannot decide whether they want to vote or not because of bureaucratic red tape has consequences for the democratic quality of the election,” said Martinez.

The agreement is also vague about the prospect of banned candidates participating in the general election. Some of the leading opposition figures, including primary frontrunner Maria Corina Machado, have been barred from holding public office, due to their critical stance towards the Maduro government.

Machado is on Sunday’s ballot, as the primary is being organised without state sponsorship. But if she or another banned candidate were to emerge as the primary winner, they would likely be blocked from running in the general election.

That leaves the opposition with a choice, Perez explained. Either it could mobilise support for the barred candidate or choose an alternative to run.

Serrano, who is voting for primary frontrunner Machado, knows her candidate may be unable to compete in the general election. But she insists on voting in the primary, saying that it symbolises her ongoing struggle for a better future in Venezuela.

“It means that there is still hope, that we haven’t given up,” she said.