As weapons taboos shatter, Kyiv and the West become strong allies

Military aid has helped Ukraine leap into the Western fold – precisely the outcome Russia had sought to prevent.

Russian President Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine a year ago insisting that he was reclaiming a historic part of Russia. The war that ensued was, in his terms, a civil war among Russians.

It was also largely a civil war among Soviet-era systems.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUkraine war will ‘never be a victory for Russia’, Biden says

Xi Jinping to visit Moscow for summit with Putin: Report

Russia’s military brass accused of ‘treason’ by Wagner chief

In a war in which both sides relied on Russian ammunition and systems, Russia had the clear resupply advantage.

The West’s determination to prop up Ukraine’s arsenal meant that it had to transition Ukraine to Western systems.

European Council President Charles Michel recently described what an unprecedented decision this was for Europe.

“When [Ukrainian] President [Volodymyr] Zelenskyy called me on February 24th, he said, ‘Charles, we need weapons. We need ammunition.’ Three days later, we formally decided to provide – for the first time in EU history – lethal equipment to a third country,” Michel told the Ukrainian parliament on January 19.

But that created a dilemma.

How far and how fast should the West go in opposing Russia in a proxy war – especially one few people at the outset felt Ukraine could win?

According to Russian principles on nuclear deterrence, Moscow may retaliate if it is targeted with a nuclear attack or may use nuclear arms if a conventional assault “threatens the very existence of the state”.

“[Russian] doctrine is that it will use nuclear weapons to de-escalate when the war is escalating and not going well,” said Colonel Dale Buckner, a former United States special forces commander with extensive intelligence experience who now runs Global Guardian, a multinational security consultancy.

“In order to de-escalate, [the Russians] will escalate using chemical or nuclear weapons,” Buckner told Al Jazeera. “It’s a written document. That is the Russian protocol, which then puts fear in everybody.”

Russia’s nuclear threat abated towards last autumn as India and China, its nuclear-armed allies, discouraged any nuclear reprisals.

But in the meantime, Russia played on Western fears.

An incremental build-up of confidence

The West moved slowly at first, providing only defensive weapons to Ukraine, but its inhibitions have evaporated due to a series of turning points in the war.

The first coincided with the defeat of Russia’s original war aims soon after the war had begun.

Ukraine used US-made Javelin missiles to skewer a 65km (40-mile) column of Russian armour as it tried to reach Kyiv.

A month into the invasion, Putin withdrew his forces from the northern territories after suffering enormous losses to focus on the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk.

NATO then sent anti-ship Neptune missiles, which Ukraine used to sink the Russian Black Sea flagship Moskva on April 24, pushing back other Russian ships 100km (62 miles) from Ukrainian shores.

The second turning point came in response to Russia’s high-intensity warfare in Luhansk and Donetsk in the Donbas region.

“Russian artillery were firing around 20,000 rounds per day, with their peak fire rate surpassing 32,000 rounds on some days,” a report by the Royal United Services Institute said. “Ukrainian fires rarely exceeded 6,000 rounds a day, reflecting a shortage of both barrels and ammunition.”

In April, allies for the first time provided armoured personnel carriers, long-range howitzer artillery and Phoenix Ghost kamikaze drones. M113 armoured personnel carriers and Mastiff heavily armoured patrol vehicles were the first Western-designed and -built armour to go to Ukraine.

Guided artillery rockets turn the war

In one of the most consequential decisions of the war, US President Joe Biden on May 30 approved sending High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems, or HIMARS, a GPS-guided multiple rocket launch system with three times the range of field artillery and an accuracy of two metres (2.2 yards) at 80km (50 miles).

HIMARS arrived in Ukraine on June 23, and two days later, Ukraine put it to devastating use, targeting Russian command posts and ammunition depots far behind the front lines in what Australian Brigadier General Mick Ryan called a “strategy of corrosion”.

After the US decision, Britain and Germany readied European adaptations of HIMARS with twice the firepower. The M270 entered into service on July 15 and the MARS II on August 1.

By late July, Kherson administrative adviser Sergey Khlan said “a breakthrough has occurred in the course of hostilities. We see that the Armed Forces of Ukraine have begun counteroffensive actions in the Kherson region.”

By destroying Russian supply lines and warehouses, Ukraine neutralised the main Russian advantage – firepower. Moscow was forced to draw its depots back into Russia and turn to Belarus and North Korea for more ammunition.

In the first week of September, Ukrainian forces were able to launch counteroffensives in the southern region of Kherson and the northern region of Kharkiv almost simultaneously, winning back territory.

Moscow Calling, a Russian military reporter, called the effect of HIMARS and similar systems “colossal”.

“Russia goes into a defensive posture, and everyone starts to realise the Russians have real problems,” Buckner said. “‘We can pin Russia’ is what a lot of people are thinking.”

Tanks and the problem with Germany

Ukraine’s ability to take back half the land Russia had occupied at the beginning of the year encouraged thoughts of offensive weapons.

“The tank is a weapon of assault and attack and advance. … They’re not defensive,” Chris Yates, a retired British tank commander with battlefield experience on the Challenger 2, told Al Jazeera.

“It’s symbolic that the West supports a Ukraine going into the assault, hitting back against Russia, not just minimising or containing a Russian advance,” Yates said.

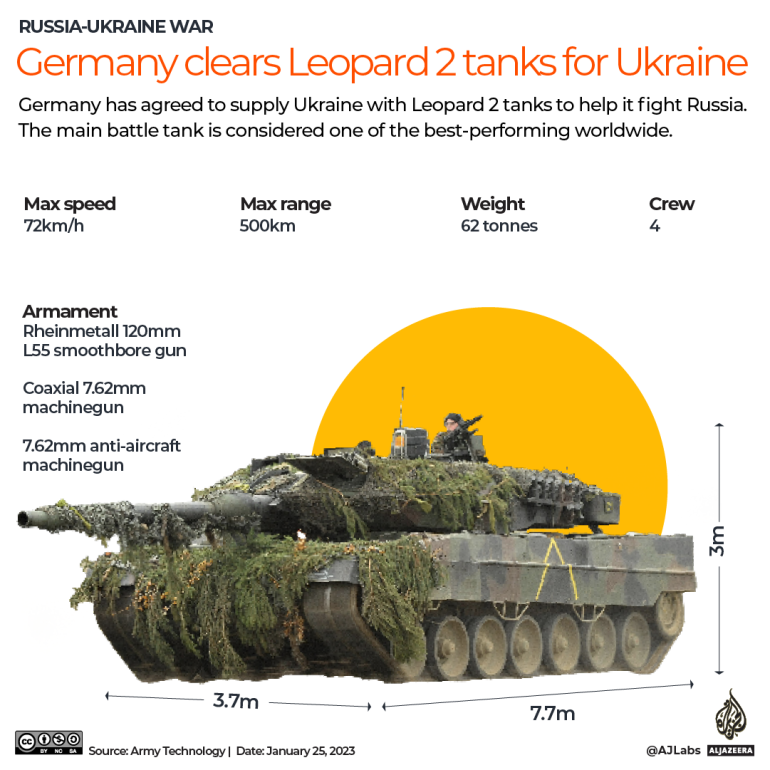

Europe’s most widely used tank is the Leopard 2, built by Germany, which needed to authorise its re-export from its allies to Ukraine, but Germany’s resistance to first-mover status was never overcome. Britain had to commit Challenger 2 tanks and the US M1 Abrams tanks for Germany to agree to allow NATO allies to export Leopard 2 tanks to Ukraine on January 25.

Allies have so far promised 223 Western main battle tanks, marking a fifth turning point in the war.

A sixth came on February 3, when the US agreed to supply Ground Launched Small Diameter Bombs (GLSDB), giving Ukraine twice the striking range of HIMARS.

Will the fellowship hold?

There are practical concerns to this military aid.

Ukraine is rapidly depleting its allies’ reserves of NATO artillery shells, and defence industries need time to ramp up production.

“States [are] either hiring local or foreign workers, adding production lines, building new plants, especially in Eastern Europe, all to increase productivity, which combined will in time make a difference, but the time it will take to reach and sustain the levels of ammunition that Ukraine is using – I have a fear that it might not be enough,” said Elisabeth Gosselin Malo, a Canadian defence correspondent.

The US announced in January that it was increasing shell production sixfold to 90,000 a month, but that will happen over a two-year period, Malo said.

“Defence manufacturers are being for the most part transparent about the numbers they’re hoping to reach, but the inventory that states have is completely off the record, so there’s not really a way for us to verify if they are in a position to sustain this for another year,” Malo told Al Jazeera.

An unnamed senior White House official told The Washington Post that Ukraine might not enjoy current levels of support indefinitely, a reference to declining Republican support for Ukraine in Congress.

Others dismiss those political concerns.

“No matter what the rhetoric is on the far right, … I think we’re all in here, and we’re going as if Putin is going all in and this is going to be going on for a few more years,” Buckner said. “… That’s the mentality in [the US Department of Defense] right now.”

“The US is going to do what it does well – we throw money at problems,” he said, a reference to the $112bn the US Congress approved last year in aid to Ukraine.

“We are ramping up to be sustainable and get our stockpiles [up] not only to support the Ukraine in the long haul but also fight a kinetic war in Asia” he said.