Mass arrest at LGBTQ club in Venezuela prompts outcry over discrimination

Recent arrest of 33 men increases criticism of President Nicolas Maduro’s overtures to anti-LGBTQ religious groups.

It was an otherwise ordinary night at the Avalon Club, a bar and sauna popular with the LGBTQ community in Valencia, Venezuela’s third-largest city.

Music was playing, drinks were flowing and guests were enjoying the accommodations, which included a restaurant, smoking room and massage parlour.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsVenezuela’s Maduro meets Lula in Brazil as relations improve

How are US sanctions affecting life in Venezuela?

But that evening, on July 23, police would burst into the club, propelling the venue and its patrons into the national spotlight — and sparking questions about LGBTQ discrimination in Venezuela.

Patrons would later recount how the police arrived shouting, “Hands up!”

“I was having a drink with some of my best friends,” one guest, Ivan Valera, later told local media. “I thought it was a joke.”

But the officers proceeded to round up the 33 men in the establishment and hold them in the sauna’s locker rooms.

Luis – who asked to be identified by his first name only, to protect his privacy – told Al Jazeera that the police said they were conducting a “routine inspection”.

“At that moment I was calm,” he said. “I simply thought that it was a normal police procedure.”

But then the officers took Luis and the other men to police headquarters in Los Guayos, a municipality adjacent to Valencia. The men were not told what crime they were being charged with, Luis said. On the contrary, they were told they were “witnesses”.

“That’s when I began to question what was happening,” Luis told Al Jazeera. “Because why are we going as witnesses? Witnesses to what?”

Only after he was forced to give up his mobile phone and have his picture taken did Luis realise he was under arrest.

“[The police] said I have the right to a phone call,” said Luis. “That’s when I started to feel disoriented, like, what’s happening? They didn’t even tell us we were arrested.”

Being gay is not a crime in Venezuela. But the men were eventually charged with “lewd conduct” and “sound pollution” among other counts. The police offered images of condoms and lubricant as evidence for the supposed crimes.

In addition, the men’s photos were leaked to local media, where they were accused of participating in an “orgy with HIV” and recording pornography. Some of the men, like Luis, had not previously gone public with their sexuality.

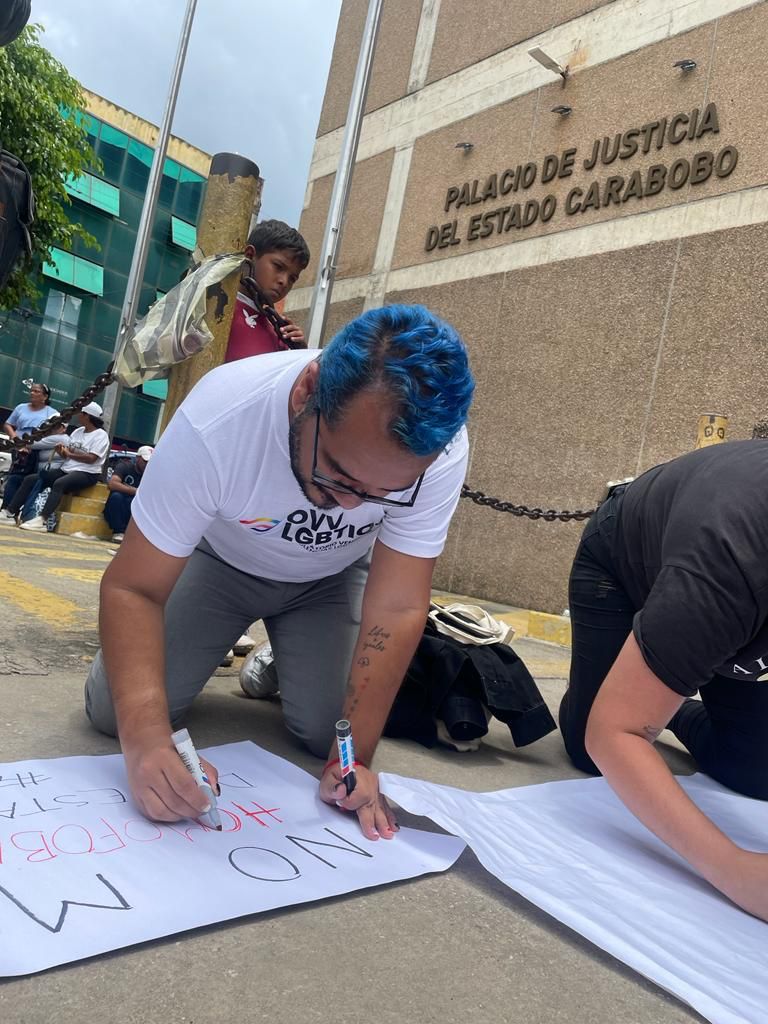

But the backlash to the mass arrest was swift. Protests broke out in Caracas and Valencia, with demonstrators calling for the men’s release. The hashtag #LiberanALos33, or “Free the 33”, also went viral on the social media platform X, formerly known as Twitter.

Thirty of the men were ultimately released on “conditional parole” after 72 hours in custody. The other three — the owner of the Avalon Club and two massage specialists — were let go 10 days after their arrest.

The Public Ministry of Venezuela and the Valencia Police did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

But Tamara Adrian, Venezuela’s first transgender legislator and a candidate in the 2024 presidential elections, told Al Jazeera she worries about the long-term effects the arrests may have on LGBTQ rights.

“Well, the truth is that this type of action, in the Venezuelan context, sends a very powerful message to the police and sends a very powerful message to judges that LGBT people can be persecuted for being LGBT,” she said.

She also tied the arrests to efforts under President Nicolas Maduro to rally support among evangelical Christians, some of whom hold anti-LGBTQ views. Evangelicals make up at least 17 percent of the country.

“Madurismo and Chavismo are having their worst moment,” Adrian said, using terms that refer to political movements under Maduro and his predecessor, Hugo Chavez. She believes Maduro is courting evangelicals to bolster his flagging approval ratings.

Last month, for instance, legislators from Maduro’s party, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), struck a deal to consult with religious groups on legislative initiatives that involve family-oriented policy.

The president’s son, Nicolas Maduro Guerra, who assumed the position of vice president of religious issues for the PSUV last July, was among the leaders who met with the religious organisations.

The agreement came after evangelical churches and socially conservative groups staged protests and parades promoting “family” values as a reaction to Pride Month, the annual LGBTQ celebration.

For Yendri Velasquez, a Venezuelan LGBTQ activist, recent events signal a deepening relationship between evangelical groups and the Maduro government.

“Principal representatives from the state are forming an electoral alliance with anti-rights groups,” Velasquez said. “I believe the arrest of the 33 people is an escalation of the political homophobia and transphobia that already existed.”

While last month’s mass arrest in Valencia was notable for the number of people detained, it was not the first time LGBTQ people have been arbitrarily detained in Venezuela.

Between January 2021 and December 2022, the nonprofit Observatorio de Derechos LGBTIQ+ documented 11 arbitrary detentions of LGBTQ people carried out by police and state security forces.

Four of the cases included acts of extortion, torture and violence including physical, verbal or psychological abuse. The organisation also found four police raids on LGBTQ leisure spaces during that time.

“Over [the last] 20 years, there has been no change for the LGBT community,” Laura Dib, the Venezuela program director at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), told Al Jazeera.

Dib attributes the lack of progress to a “democratic back-sliding” thanks to Chavez, Maduro and the closure of organisations that face alleged state intimidation, like human rights groups, independent radio stations and news outlets.

“If you take a look at discussions in the legislature over the past 20 years, there has been next to no discussion on matters such as sexual and reproductive rights … and protection of LGBTQI rights,” said Dib. “And this is a result of the closure of civic spaces and the persecution of human rights groups and human rights defenders.”

Venezuela remains one of South America’s most conservative countries for LGBTQ rights. It is one of the few countries in the region — along with Peru, Paraguay, Guyana and Suriname — that offer no legal recognition for same-sex couples. And transgender individuals still cannot legally change their gender on official documents.

Though Venezuela has some laws to prevent discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, critics say they are rarely enforced in practice. In the case of the 33 men from the Avalon Club, Venezuela’s Attorney General Tarek William Saab has recommended the charges be dropped.

But the experience has shaken Luis’s hopes for the future of the LGBTQ community in Venezuela.

“[What happened] to us kind of reaffirms that, here in Venezuela, we are not all equal,” he said. “Here there are no rights, here there is no equality, and this confirms it.”