Ukraine, Russia fight from the skies as Kyiv’s EU aid hangs in the balance

As a key summit focuses on aid, Russia says it will increase air defence missile production as air wars are fought over Ukraine.

The European Union is gripped by a crucial summit on Thursday that will be dominated by a second attempt to pass a 50-billion-euro ($54bn) amendment to the bloc’s budget that will help finance Ukraine over the next four years.

That amendment was vetoed by Hungary at last December’s regular summit, along with 20 billion euros ($22bn) in military aid to Ukraine for 2024.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRussia and Ukraine complete first prisoner exchange since plane crash

Is Zelenskyy planning to fire Ukraine’s popular top army commander?

ICJ rejects most of Ukraine’s ‘terrorism’ case against Russia

The EU’s executive, the European Commission, was reportedly hoping to bring Hungary on board by offering Prime Minister Viktor Orban an opportunity to block a continuation of the support next year, when the EU would re-evaluate whether Ukraine still meets the requirements to receive the money.

That tenor of conciliation changed by Sunday, when the Financial Times reported the EU also had a plan to sabotage Hungary’s economy if it refused to cooperate.

Details of the plan were secret, but the EU has leverage.

Its internal market buys roughly 90 percent of Hungary’s exports, and the EU is withholding 30 billion euros ($32bn) in aid to Hungary, of which it promised to release 10 billion euros ($11bn) last December in return for Orban walking out of the room where the remaining 26 heads of government voted to give Ukraine and Moldova official candidate status to the EU.

Orban’s political director said Hungary was ready to consider cooperating on Monday and Orban reportedly confirmed that in remarks to Le Point on Tuesday. But EU officials said a deal was still uncertain.

Meanwhile, a $60bn US aid package to Ukraine remained stalled in the US Senate, where Republicans loyal to presidential hopeful Donald Trump were reportedly holding out for a deal with the administration of President Joe Biden on border security with Mexico.

The EU’s foreign policy chief, Josep Borrell, said the bloc was close to agreeing to a 5-billion-euro ($5.4bn) emergency funding stopgap from its European Peace Facility. “The moment has not come to weaken our support to Ukraine … we need on the contrary to do more and faster with financial resources, with military equipment, by training soldiers,” Borrell said.

The EU established the EPF in 2021 to help finance global military operations.

EU aid is crucial to Ukraine, which faces a $43bn budget deficit this year, and expects to cover $41bn from international aid.

War in the air

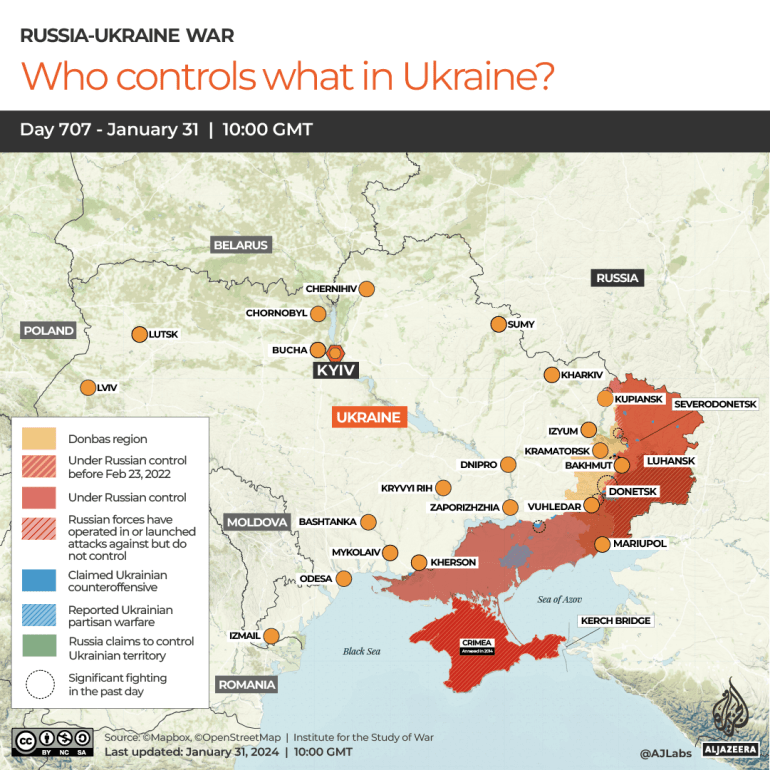

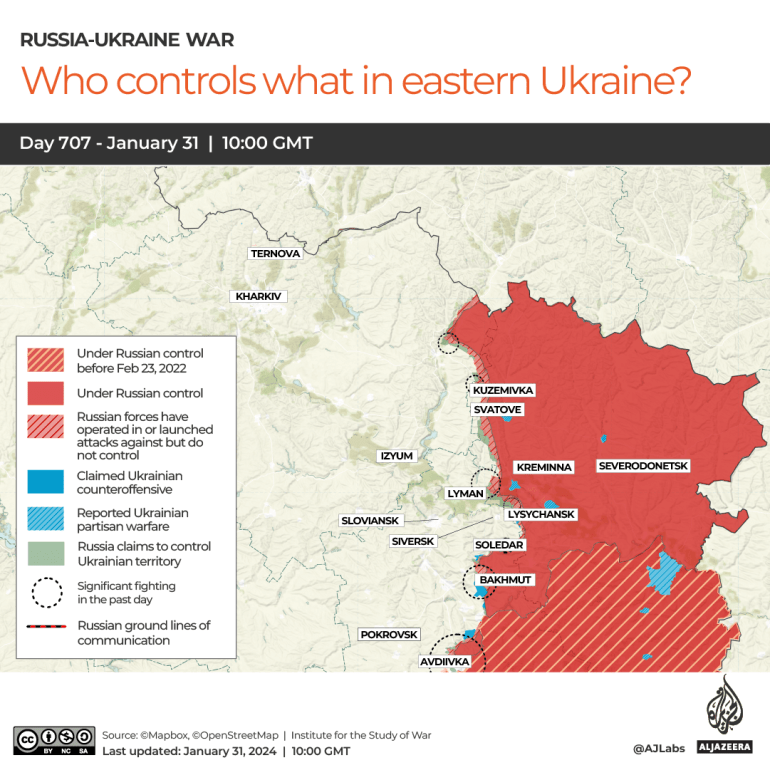

Ukraine said a Russian winter offensive to recapture lost territory in Kharkiv and Luhansk, and to complete the conquest of Donetsk, was ongoing. But most of the action was in the air – some of it focused on the line of contact as part of a Russian effort to hobble Ukraine’s defences.

In a rare appearance touring defence industries, Russia’s Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu said he hoped to increase the production of air defence missiles, used to intercept drones, missiles and planes.

He said air defence missile production had already doubled during the Ukraine war, but that was not enough.

“There are some key issues we need to address … There is the question of engines, and there is the question of the establishment of launcher production,” Shoigu said in the Urals city of Yekaterinburg.

Shoigu’s comments came as Ukraine seemed to have scored a new hit against a Russian target.

Geolocated footage showed a fire at the Rosneft oil refinery in Tuapse, on the east coast of the Black Sea, on January 24. The Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) claimed responsibility for the attack. Local residents reported several explosions, and footage showed drones had been operating in the area.

The SBU has been developing long-distance surface and air drones, and used them successfully to attack Russia’s Black Sea Fleet and targets in Crimea. This year, it has focused on energy infrastructure. On January 21, it struck a Novatek gas condensate processing plant near Saint Petersburg.

Russian authorities said they had downed 21 Ukrainian drones launched against Crimea on January 30.

Russia, too, continued waves of missile and drone strikes against Ukraine, which it has sharply stepped up since December 29. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said Russia had launched 330 missiles and 600 drones this year.

On January 25, Ukraine shot down 10 out of 14 Shahed drones launched by Russia. Four S-300 missiles got through. Three days later, Ukraine shot down four out of eight Shahed drones launched by Russia and a Kh-59 cruise missile. Two Iskander missiles and three S-300 missiles got through.

Ukraine said it downed all eight Shahed drones launched the following day, but six S-300 missiles got through. The biggest barrage came on January 30, when Ukraine shot down 15 out of 35 drones along with two S-300 missiles.

The cyberwar

Ukraine’s military intelligence said it scored a big cyber-victory in Russia’s far east. Its cyberattack against the Russian “Planet” Scientific Research Centre of Space Hydrometeorology’s far east branch destroyed the centre’s 280 servers.

Ukraine estimated it had destroyed 2 petabytes worth of “unique research developed over the years”.

Ukraine’s military intelligence (GUR) said the centre received satellite data and provided information to at least 50 Russian government agencies, including the Ministry of Defence (MoD), which in turn passed it on to defence contractors.

“Dozens of strategic companies of the Russian Federation, which work for ‘defence’ and play a key role in supporting the Russian occupation forces, will remain without critically important information and services for a long time,” GUR said.

GUR estimated it had done $10m of structural damage through lost servers and software, which cannot be replaced under sanctions. Russia has proven quite adept at circumventing sanctions so far.

Bloomberg News cited classified Russian customs service data showing that Russia had imported $1bn worth of US and European microchips last year despite sanctions – down from $2.5bn in 2022 but still sizeable.

The information war

Russia was active in the information sphere.

Geolocated footage posted on January 24 showed a Russian Ilyushin-76 transport plane crashing in Belgorod, a Russian region bordering Ukraine.

The Russian MoD said Ukraine had shot the plane down using two air defence missiles tracked by Russian radar, killing its six crew, three military personnel and 65 Ukrainian prisoners of war intended for an exchange.

“The Ukrainian leadership knew very well that, according to established practice, today Ukrainian military personnel would be transported by military transport aircraft to the Belgorod airfield for exchange,” Russia’s MoD said.

“According to the previously reached agreement, this event was to take place in the afternoon at the Kolotilovka checkpoint on the Russian-Ukrainian border.”

Ukraine shot the plane down regardless, Moscow said, “pursuing the goal of blaming Russia for the destruction of the Ukrainian military”.

Russian President Vladimir Putin repeated the allegations two days later.

Ukraine’s military intelligence confirmed a prisoner exchange was to take place and said it was investigating the circumstances of the crash.

Russia might have had a motive for an information campaign in which it accused Ukraine of “terrorism”.

The top court of the United Nations, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), will rule on Friday whether Russia violated international law by invading Ukraine.

Ukraine brought the case to the ICJ days after the February 2022 invasion, arguing that Russia broke international law by falsely claiming genocide against ethnic Russians living in Ukraine as a basis. Russia unsuccessfully tried to have the case thrown out.

If the ICJ rules against Russia, it will be its second high-profile condemnation after convicting Putin in March last year as personally responsible for organising the kidnapping of Ukrainian children.