Picturing the Prophet Muhammad

Iran and Qatar are producing big budget films on prophet’s life amid increasing Islamophobia.

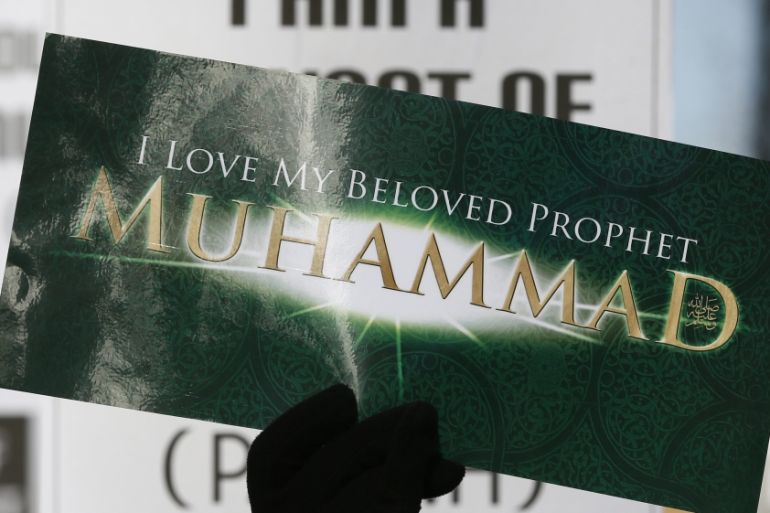

The news that a leading Iranian film-maker Majid Majidi is about to release his biopic on the life of Prophet Muhammad reached the global media at a time when, in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, the world was alerted to a critical aspect of Islamic theology: Irrespective of the attitude and politics of the matter, can the prophet be visually represented?

That now a Muslim was engaged in making a movie about the prophet put a critical twist to that question. If Majidi were to be marked as an Iranian or a Shia, then the figure of the late Hollywood-based Syrian film-maker Moustapha Akkad would immediately come to mind who long before Majidi also made a film on the same subject: “Muhammad, Messenger of God” in 1976.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUS returns ancient artefacts looted from Cambodia, Indonesia

Mandela’s world: A photographic retrospective of apartheid South Africa

Portrait by Gustav Klimt sells for $32m at Vienna auction

In the same news item that we learned about Majidi’s film, we also learn that the Qataris are upping the ante on perhaps regional rivalry and producing their own even more expensive film version of the prophet’s life – with Barrie M Osborne of “the Lord of the Rings” named as the producer.

Central historic figure

Thus the matter of film versions of the Prophet’s life has clearly crossed all national, regional, and sectarian divides. Muhammad is a central historic figure at the heart of a worldly religion over which Muslims believe shines a transcendental God beyond time and space, proportion and materiality.

|

|

All of these cinematic adventures now take the life of the prophet out of the sacred memories of millions of Muslims and brings it straight into not just the geopolitics of the region, but also, the widening domain of the North American and Western European escapades in Islamophobia.

Majidi’s biopic enters not a vacuum but a real world inundated with decidedly hostile pictures of Muhammad and his message. Based on a script by the notorious Islamophobe, the Somali born Dutch politician Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the Dutch film-maker Theo van Gogh also made a short provocative video in 2004 called “Submission” in which the film-makers depicted the prophet’s sacred legacy, the Quran, in an unsavoury light.

As Hirsi Ali was accused of plagiarising the work of the prominent Iranian artist Shirin Neshat, her collaborator Theo van Gogh was assassinated by a Dutch Muslim in Amsterdam.

With such hallmarks of Iranian cinema as “Children of Heaven”, “The Colour of Paradise”, and “Baran” to his name, Majidi’s cinema is marked with lush visual tapestry, mystical narrative tropes, and loving camera work cozying up to his endearing characters.

Majidi’s cinema is thus entirely different from anything that Hirsi Ali or her kindred soul, the convicted crook Nakoula Basseley Nakoula, did when he produced a film called “The Real Life of Muhammad” aka “Innocence of Muslims”, or “Innocence of Bin Laden”, that also caused protests in many countries and made the headlines at the time.

Beyond anyone’s claim

From Hollywood crooks to French cartoonists, from Dutch politicians and plagiarists to major Iranian film-makers, from mega-million dollar budgets allocated by Qatar to world renown producers to revered Arab film-makers like the late Mustapha Akkad, we have now seen varied interests in the life of the prophet.

Majidi has evidently opted not to show Prophet Muhammad's face in order to avoid irking orthodox sensibilities...

Beyond the obvious distinction between racist provocations on one hand and pious homage on the other, distinguishing these varied receptions of the prophet’s life and character, one other towering fact emerges: The life of the Prophet of Islam has now entered a global scene far beyond anyone’s claim or control.

It is upon that tumultuous transnational public sphere that Majidi’s new biopic on the life of the prophet is being produced and released. Designed to be a trilogy, the first part of the projected film covers the prophet’s youth.

Majidi has evidently opted not to show Prophet Muhammad’s face in order to avoid irking orthodox sensibilities (both of the Sunni and the Shia ranks), though there are widely available popular renditions of the prophet’s imaginary visage.

According to reports, none other than the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic himself, Ayatollah Khamenei has visited the site of Majidi’s production near Qom – though he has done so secretly perhaps because they did not want to irk the former president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who might start making a federal case about Majidi’s short lived dalliance with the Green Movement when he made a campaign film for Mir Hossein Mousavi. But that news of Khamenei’s visit and thus approval has now surfaced is a clear indication that he is endorsing the project and thus seeks to preempt any opposition from other high-ranking clerics.

Prophet Muhammad is not a doctrinal abstraction. For Muslims around the world, he is the Messenger of the one and only true God who is beyond all visibility and materiality. Muhammad was a mortal human being with immortal attributes, and as such, the absolute metaphor of a people who know, recognise, and pride themselves to be Muslims. Cinematic, visual, dramatic, poetic, and even the protests against controversial portraits of the prophet are all signs and signals of a new generation of Muslims trying to imagine their own better angels in light of their prophet for their posterity.

Hamid Dabashi is Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.