Soumahoro: The migrant who can save the Italian left

The migrant trade unionist has all the tools necessary to defeat PM Meloni’s far-right populism and finally revive the Italian left.

Late last month, Brothers of Italy leader Giorgia Meloni finally managed to form a coalition government, officially adding her country to the ever-growing list of European nations led by far-right populists.

In their coverage of Meloni’s ascent to power, most Italian and international media organisations understandably focused on her apparent admiration for Italy’s former dictator Benito Mussolini and Hungarian far-right leader Viktor Orban, as well as her coalition partners’ perceived support for Russia’s Vladimir Putin.

Nevertheless, now that the Meloni government is officially in power, there is an urgent need to change the focus of this conversation, and start talking about who should be leading the opposition against the most right-wing government the country has had since the second world war.

With the centre-left divided and in perpetual crisis, none of its well-known leaders appears remotely capable of forming an effective opposition movement against the far-right government.

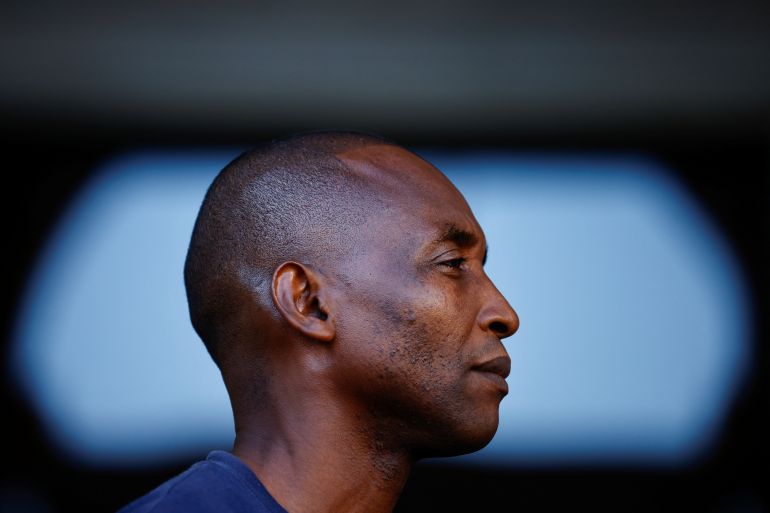

There is, however, one progressive in the new Italian parliament who has a real chance of reviving the long-flailing Italian left and forming an opposition movement that can actually pose a meaningful challenge to Meloni: migrant union leader Aboubakar Soumahoro.

Soumahoro, 42, is an Ivory Coast native who migrated to Italy in 1999, aged 19, with the dream of building a better life in the country. After sleeping rough on the streets of Rome for some time, he eventually managed to overcome the many obstacles to migrant success in Italy, became an Italian citizen and completed a degree in sociology at the University of Naples.

Within a few years of his arrival in Italy, he also became an activist helping migrants without official documents, focusing on the exploitation of farm labourers. He subsequently founded a union representing exploited agricultural workers. Through this union, he organised protests against the “caporalato,” an illegal system to outsource the recruitment of labourers to gang leaders. These experiences helped him realise that anti-migrant politics hurt not only migrants but all workers, and encouraged him to run for office.

In the September 25 election, he won a seat in the lower chamber of the parliament on the Green and Left party ticket, becoming the only Black politician in a parliament dominated by far-right nationalists. In his first speech in parliament, underlining his immigrant roots, he reminded Meloni that “one is not only born Italian but also becomes Italian,” and reiterated his intention to use his new position to speak for the poor and the disenfranchised.

What sets Soumahoro apart from other leftists in parliament and makes him the perfect candidate to lead the opposition against the Meloni government is not only that he is a successful migrant unionist and left-wing activist who personifies everything this government stands against and seeks to destroy, but also that he appears to understand how populism can help the fight against fascism in Italy.

In the late 20th and early 21st century, technocratic governments designed to defend the neo-liberal status quo against threats from both left and right-wing ideologies started to form across Europe. Against the policies implemented by these out-of-touch technocrats – which led to an unprecedented increase in social and economic inequality in many countries – different populist movements started to emerge across the continent. Populism, which is a political strategy that unites people around shared fears, frustrations and desires, proved successful in many contexts, mainly because it offered a return to a politics in which leaders form a direct, personal relationship with the masses.

The neoliberal establishment has been painting all types of populism, both left and right wing, with the same brush, deeming them anti-democratic and detrimental to the best interests of the people of Europe. Populism, however, is neither inherently undemocratic nor detrimental to the interests of the people. Populism has always been a core element of democratic politics and today, in the age of social media, it seems to be delivering faster and more comprehensive results than ever before.

Therefore, the question we are facing today is not whether populism has a place in democratic politics, but what type of populism we’d rather have dominate the political arena: the right-wing populism of Marine Le Pen and Viktor Orban that aims to unite angry masses against immigrants, or the left-wing populism of Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Bernie Sanders which aims to create a united front against transnational corporations and other destructive forces of neoliberal globalisation.

The neoliberal establishment, which drove the world into the crisis it is currently in, will not be able to counter the rise of far-right populism through its policies that increase inequality and fuel polarisation. Perhaps the only way to stop the return of fascism through right-wing populism in many Western nations is to support left-wing populist projects that target both the forces of fascism and neoliberalism.

Thus, in Italy too, the best path to defeating Meloni’s far-right populism – which presents immigrants, LGBTQ communities and feminists as enemies true Italians should unite against – is through leftist populism, and Soumahoro seems to be well aware of this.

Soumahoro not only says he speaks for the poor and the disenfranchised but in a truly populist manner calls on the populace to rediscover its emotional connection with politics – the loss of which is the main reason why representative democracies and establishment politicians are in crisis.

In his book Humanity in Revolt: Our Fight for Work and the Right to Happiness he lays out the ideological principles of his political project. He points to a link between work, happiness, and our existential condition that can help mobilise workers who are not adequately paid for their services under a leftist umbrella. He adds that this link can be established only if the Left recovers an “emotional connection with society”.

In his speeches, he often advocates for exploited workers and voices the concerns of common citizens. He also uses emotional symbols to connect with the public. He, for example, wore muddy wellies to parliament on his first day as a lawmaker to remind people of his humble beginnings as an immigrant farm worker and signal his sensitivity to the struggles of working Italians.

Despite his apparent desire to form a personal connection with the electorate, Soumahoro does not like to talk about himself. He underlines that it is “more important to talk about “us” than “I” explaining that he believes Italian politics is far too personalised. And he includes in that “us” not only workers and migrants, – people he most easily empathises with – but all groups that expect to suffer under the current leadership, such as feminists, environmentalists and LGBTQ communities.

He defines Meloni’s “Italians first” policy as a manipulation of the migrant crisis for electoral gain and claims it is going to fail as “putting Italians first is not going to pull 5.6 million Italians out of poverty”. But he refuses to merely target Meloni and insists on also analysing how the Italian left has come to ignore the problems of several groups – such as field hands, domestic workers and delivery drivers – merely out of convenience. The left is “trapped in a logic of political convenience,” he explains. “But this is the wrong logic, we should not change things to remain in positions of power but rather we should remain in positions of power to change things.”

Today, Italy is in desperate need of an opposition that can counter Meloni’s nativist policies. Even more importantly, the country needs an opposition that can connect with the masses and give them a reason to trust and support the left once again. Soumahoro, as an immigrant unionist and a gifted politician who understands the value of populism, is the best person to build that opposition.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.